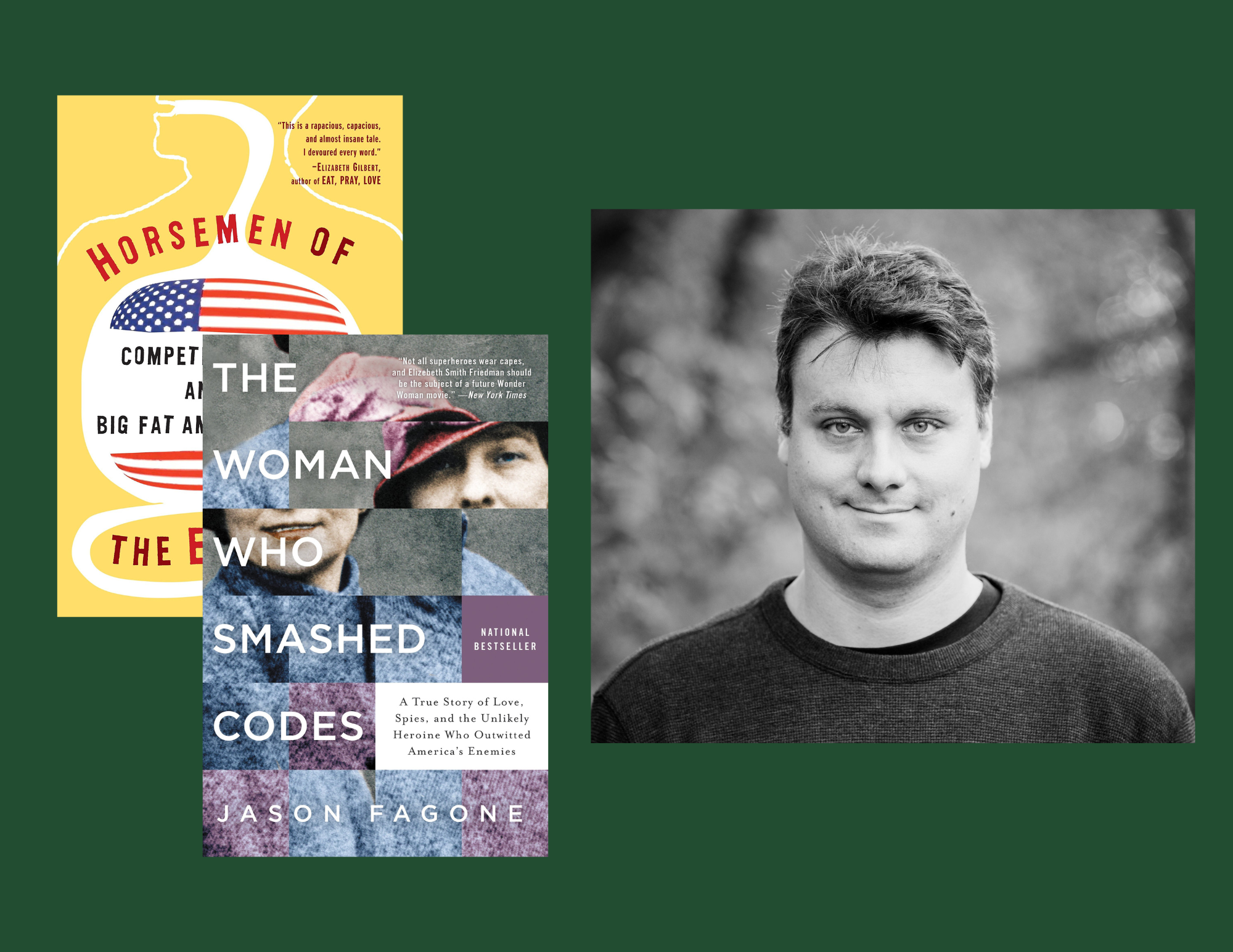

Jason Fagone is an investigative journalist for the San Francisco Chronicle, who previously lived and worked in Philadelphia before relocating to the Bay Area. As a non-fiction writer, Jason is both a journalist and author of three books: Horsemen of the Esophagus, Ingenious: A True Story Of Invention, Automotive Daring, And The Race To Revive America, and his most recent book The Woman Who Smashed Codes.

I had the chance to talk to Jason about his books and journalistic work.

Randee Wismer: I wanted to start off by asking you some questions about your books! You’re a nonfiction writer and your book topics seem to span some pretty different niches—you have a book about a woman spy decoder, a book about competitive eating, and one about car inventions and innovations. I was wondering how you choose, or come into, these stories and topics?

Jason Fagone: That’s a good question. There’s not a formula. I kind of wish there was because that would be a lot easier. But it’s usually a combination of luck and work, and some kind of instinct that draws me to a story initially and then compels me to keep going back and learning more. I think, a lot of the time, what happens is I’ll meet someone who is interesting to me, and I start talking to them, and I realize they’re part of some world that I want to know more about, or have access to a world that most people don’t have access to and they have this unique perspective on it. And so by spending more time with that person I can, kind of, learn more about that world. An example is, the competitive eating book. I met a guy, Bill “El Wingador” Simmons, in Philly and he was the 4-time chicken wing eating champion of Philadelphia, of the wing bowl. He was going for his fifth wing bowl, and he was just starting his training process for that. I knew nothing about competitive eating, I had only ever thought it was kind of ridiculous. But through Bill I had an opportunity to learn more about it, and I just followed him as he prepared for [wing bowl] number 5, and it turned out that Bill opened the door to this huge, bizarre world of eating that was becoming super corporatized and that was fascinating to me. So that was my way in.

RW: What makes something capture your attention enough to write about it?

JF: Again, I don’t know if there’s a formula. I think it’s more a matter of taste. I like this kind of food, not that kind of food. This kind of music, not that kind of music. And I don’t really know why I like this kind of food, I just kind of do. And I trust it at this point because it’s part of my personality. I know that’s a really vague answer. I guess, more concretely, I do have story subjects that I’m interested in and track actively. I keep an eye out for news about them and try to find a way in or something I think I can offer. Maybe I’m interested in surveillance technologies by police departments, so I make a news alert and then I read anything that’s coming out about that topic. A lot of the times what will happen is there will be an interesting criminal case that might have broader implications, or some kind of lawsuit or conflict, and I make a note of it and I wait. Because there’s usually a lot of initial news coverage about something and then it dies down and then a week or two later, when everyone else has gone, I can go in and start talking to people and try to do a deeper story. And at that point, sometimes folks are more willing to talk, so that’s how a lot of stories and books begin for me.

RW: You’ve written about some hot debate topics such as shootings and marijuana advocacy and policy changes. I felt as a reader that I could see some politics bleed through these pieces. I was wondering if you feel that you bring activism into your work? Or if you’ve seen your work impact activism efforts?

JF: I mean, I’m definitely not an activist. I do not set out to achieve a political goal of any kind. I’m not explicitly trying to change legislation for example, or get people to support one politician instead of another. That’s never the point. That’s not the point of the kind of journalism I do, anyway. The point is really to tell some true story about how the world really is, and leave a record of something that feels important to me. And people can use that information however they will. That’s not to say that these stories are written from a neutral perspective. Long-form journalism, the kind that I do, is always written from some perspective. They’re not a robotic list of facts. They begin with a perspective and they explore. A good example is a story I did about a trauma surgeon at Temple.

RW: Yes, that was hard.

JF: It was a hard read, hard to report, and a really hard job that she has–treating hundreds of gun violence victims every year, year in and year out, for 30 years. But that experience had given her a totally unique perspective on this big problem that America has with gun violence. So that story began from the perspective that a problem exists and now we’re going to try to see that problem through the eyes of this person who has a completely vivid and important window onto it, and we’re just going to follow them, look over their shoulder, and try to understand it through their eyes.

RW: On the topic of hard stories, how do you approach writing about sensitive topics? Do you have to create a certain space for yourself, a routine, when you’re working on something like that?

JF: I think the routine is pretty similar for any story, no matter the sensitivity. If it’s a story where there are sources who are anonymous, because they’re being targeted online or otherwise or they’re afraid of consequences, and I’ve agreed to grant them anonymity, then in that case, I take extra precautions around note-taking and that kind of thing. But the basic routine for reporting and writing is usually the same. And it’s totally not glamorous, right? It’s not something that would ever be filmable [laughs]. It’s not like—it’s very funny. Most of the journalism movies are great, I love them, but they make the journalistic act look much more glamorous than it really is. A lot of it is just compiling information and typing when you’re not out in the field talking to people. So the routine is the unglamorous part about it. The more it stays the same across the stories, the more reliable it will be and the better your—at least for me, it feels like the better I’ll be able to complete the work at a decent level.

RW: For a more sensitive or harder piece, in comparison to something more “low-stakes”, do you feel that you have to give yourself more time?

JF: Especially if the stakes are high personally for someone who’s talking to me, if there’s potential for them being attacked or if their life might change in some way by publicly participating in the story and being named, then yeah, absolutely. There’s more work involved in talking to that source, talking to other sources that might impact it. Throughout the process, not just at the beginning, but checking back in with them after the interview and keeping them in the loop about what’s going on with the story. Making sure they’re comfortable with how they’re being quoted and the context of it all. And I think that, for stories that are higher space in that sense, then I do spend more time immersing myself in a subject, researching and reading, being there on the ground. For example, the trauma surgeon story, I wanted to make sure—Dr. Goldberg invited me to shadow her on a couple of her shifts. I watched her, but I didn’t feel that I was necessarily getting a complete enough picture of what her work and experience was like, so I kept going back. And she was very gracious with her time and kept inviting me back. So I ended up going to several shifts at different period of the day, different times just to make sure that I got a more complete picture of what was going on there because it did seem like it was really important to capture some accurate or representative slice of life in that active and busy trauma work.

RW: How do you handle the emotional labor of researching and writing about sensitive topics?

JF: It used to be, at least when I was younger, that the industry had a very different stance about it. And what they would tell you in school was very different, what you would hear from colleagues is very different. I think 20 years ago, you were kind of just encouraged to suck it up, right? “Don’t complain, it’s part of the job.” I’m sure there’s all kinds of other things I heard and absorbed as a young journalist that are like that. It was more like, this is part of the job and you’re not supposed to feel it emotionally. I think the industry is getting better than that. There’s still learning and progress to be made in supporting reporters and writers when they tackle really, sort of, emotionally challenging and potentially traumatic subject matter. I have colleagues at The San Fransisco Chronicle where I work who cover wildfires and that’s a really hard job, a really hard job. Because they’re going into a community where there’s just been a really tragic loss of life, and the first responders are still there. The fire might still be burning, and people have just lost loved ones. They’re going in and trying to tell the story and write and photograph while the community is still processing the grief. That is really, really hard. So I think the hope is that the industry continues to provide resources for reporters who need to talk through their experiences. It’s getting better but I think there’s still some way to go. I also, when I was younger, used to try to talk about these things with loved ones around me, which I don’t necessarily think is the best idea. Sometimes talking to professionals really helps. And talking to colleagues who’ve worked on those kinds of stories and been through it, and can give you moral support.

RW: Thank you for sharing that. To pivot, I think you’ve spoken to this, but I wanted a bigger picture on what your research process is like.

JF: It really depends for each story. It usually starts by reading everything else that everyone has written for that subject or person or world. Then I reach out to the person I’m going to be writing about, or the person who sort of knows something about the subject, to see if they want to talk, see what the access will be like. Or sometimes, if it doesn’t start with an interview like that—it might be based on public documents—the first thing I do is put in a public records request and see if I get something back or see if it’s likely that I get anything back at all. Either way, I’m kind of looking for some kind of edge. I think all reporters are looking for some way to break into a story, some kind of window or way in, that helps you advance what’s already known. It might be a person wanting to talk. It might be a stack of papers, some historical archive somewhere. Then once I feel like the door is cracked open, then I try to keep going back, and going back, and going back. I keep showing up. I’m not fast with reporting. I can be really, really, really, slow with reporting. I’m also very stubborn, extremely stubborn. I hate giving up on something that I think has potential. That’s something I’ve always done: keep flinging myself back at the wall [laughs].

RW: This question is coming from someone who is new to conducting interviews. How do you prepare for an interview?

JF: I do differently now from how I used to when I was just starting out. When I was just starting out, I would try to, kind of, exhaustively read everything that had ever been published about the person I was going to be talking with. I would get really nervous if I felt like I had missed something, if I hadn’t read every story that had ever been written about a person. Then I would make a list of questions and I would go into the interview and I would basically just read down the list of questions. Question 1, question 2, question 3. Over time, I stopped doing that so much, and I tried to, not read less, but I tried to relax if I felt like I hadn’t necessarily read every word that had been written about the person before. While I still would prepare questions for that person, I would try to look for opportunities during the interview to be open to surprise. To divert the plan for the questions down some unexpected road. To try to listen for anything weird that the person might say. It’s important to be alive to the weird, to the unexpected, and to go with that in the moment if an interview subject is willing to do that. It sounds simple to say but can be hard to do in practice. It has led to some of the best material that I’ve gotten. A lot of the time, the way that happens is by not necessarily talking yourself so much. Any journalist will tell you this, but a lot of the time we get in our own way and end up talking over moments when some interesting space might open up and can be explored. A lot of the time when I’m listening to tape, this was more true years ago, but I get mad at myself for talking. Listening back to tape with some distance, I can tell that the person was about to say something interesting, and I screwed it up by opening my mouth. Sometimes the really simple trick can be to leave moments of silence in an interview because, when two people are talking it begins to be a little bit awkward when there’s a moment of silence. And when people feel that awkwardness, they will try to alleviate the pain of that awkwardness by filling it with words. Sometimes if you just sit quiet for a couple of moments, then the person you’re interviewing will start talking and fill the space and say something interesting. You’d be surprised how often that happens if you let it. You have to let it happen.

RW: About being open to surprises, has there been a time where you felt like you knew your stuff, you were informed and prepared, and you ended up having an interview that was completely different from what you expected going in?

JF: That happened with the Temple story, the trauma surgeon story. The very first words that Goldberg said to me on my very first interview with her were totally unexpected, totally out of the blue. She confronted me immediately and said, “Your story isn’t going to change anything.” And we ended up having a conversation about that, about the pointlessness of me writing a story about her and her work. Because the legislative environment in the US around gun violence is just so paralyzed. But that actually became a really important way into the story and a starting point. Like, okay, we’re going to start from a place of futility, and now we’re going to see what we can learn. We’re going to explore this futility and let’s dig into it, see what it looks like. I tried to be open to that and it ended up providing the opening scene for the story. There was another time I went to interview a Philadelphia developer who had just written a comically large check to a local politician. The check was so large, it had gotten into the news, I think there was an Inquirer story about it. I went afterwards and everyone was curious about this developer. What was his deal, what was he all about? I went for the first interview prepared to talk to him about political donations and checks, and he wanted to talk about his new-age meditation routines [laughs]. He ended up talking about this, I don’t know if you’ve ever heard, there’s this thing people can do where they sit in an isolation tank, it’s like a pod filled with water. You sink into the water and it’s designed to be total sensory deprivation. To me it sounds like a claustrophobic nightmare, but I guess some people find peace in eliminating all sources of noise and sounds, so they can only listen to their thoughts. And he had been doing this, and his mind was just afire with the possibilities of this stuff. So, okay, well, now I can learn about this guy because he’s really interested in this new-age meditation stuff and that’s interesting and now I know something about this guy that other people don’t know. And I’m shedding a little bit of light into his soul, or his deal. More than happy to talk to him about these new-age meditation things that I had no idea about.

RW: It’s pretty clear that you’ve written about all different sorts of things. I was wondering what are some of your personal or career writing highlights?

JF: Working for city magazines in the early 2000s. That was something I loved and as I look back on it now, it seems more and more special and unique to me that that moment in time—where there was a magazine industry that could pay writers and there was a thriving set of city and regional magazines that existed entirely outside of national magazine world; where a lot of large cities had their own glossy magazine and each glossy magazine had a feature well; and there was a staff of writers on salary and freelancers that would do long-form narrative reporting and writing in that feature well. I worked for two city and regional magazines over a period of 4 years and wrote 7-10 long-form articles a year for them in my 20s. I think the issue today is that these jobs don’t necessarily exist anymore. For me, it was an amazing training ground to do what I love, to do what I wanted to do. So that was a highlight. Also, writing my first book, Horseman of the Esophagus. I did that in my mid-twenties. It was an incredible boot-camp for learning how to report and write a book. It sometimes seems to me like a weird dream that I spent 2 years immersing myself in the world of competitive eating, but it’s a fun story to tell people and I’m still really proud of the book. Also, my last book, The Woman Who Smashed Codes, has been a real highlight, an incredibly rewarding experience. I’m happy with how the book turned out, I’m happy with the response it’s gotten. There’s a whole lot of people who have read it and loved it and responded to the story of the woman at the center, Elizebeth Friedman, this incredible code-breaker. She never got the recognition that she deserved in her lifetime, but now I think, thanks in part to the book, that she’s finally being honored and appropriately remembered. There’s someone who read the book who made a statue of her. That’s amazing! The US coastguard is naming a ship after her, The Freidman. That’s being built now in Mississippi. Like a real, physical, very large government ship emerged from, at the tail-end of this process, that began with me being curious about some offhand mention of her that I read in a document somewhere. That to me has been really gratifying. The possibility that that can happen, that stories can have that kind of power, is part of what keeps me going.

RW: What’s the most rewarding thing about the work that you do?

JF: There’s a lot of things that can be rewarding about it. It feels good to tell a story that needs to be told and that hasn’t been told before. To add something to the world’s store of knowledge. It feels good to hear from sources after you wrote about them that you got something right and you treated them well, you captured something true about their lives. It feels good to write a solid sentence [laugh], right? That always feels good, that never stops feeling good, because it’s hard!

RW: Pivoting again, we are Write Now Philly! We are interested in writing and our area! I was wondering how living in Philadelphia influenced your work, writing, or writing-topic interests?

JF: I love Philly. I’ve always loved it. The city is so rich with stories. It’s a big diverse place, has a lot of challenges, a lot of characters and intense personalities, a lot of conflict. It’s central in certain national political battles. So I’ve probably been spoiled in that sense living in Philadelphia. There’s this sort of endlessly replenishing well of stuff to write about. And big characters! Big, big characters. For a magazine writer, someone who works in non-fiction, it’s a promising and fertile place to be. There’s always something to write about that matters. I also think that not living in New York, not being a writer in New York is something that has been important to me. It has helped me because so much of the industry is centered in New York—the magazine industry, even the newspaper industry, definitely the publishing industry. At one point in the 2000s, I would go to visit magazine editors in Brooklyn and I was just convinced that every magazine editor in the United States lived within a six-block radius in Park Slope. I wanted to be outside that a little, and I wanted to have a perspective that wasn’t that perspective. For me, that’s been really important, to be a writer based in Philly writing about Philly stories. I’m not right now, but I was for a long time.

RW: Thank you so much for your time! Is there anything that you’re working on now, or any work that you’d like to uplift?

JF: I’d like to uplift the work of my newspaper, the San Fransisco Chronicle, which is a really wonderful place, and a special place. I read it, I have a lot of friends and colleagues there. I read their work and I am continually impressed and often amazed by the dedication that they have to the job, to the city, and the quality of the writing and reporting and photography that they put out. It’s hard to be working in media in a lot of ways at this moment. I feel really lucky to be working at a newspaper that is hitting its stride doing great work and doing stuff that matters. And anyone that’s reading this that’s interested in the Bay Area or tech, please subscribe because we need you!

To learn more about Jason Fagone, visit his website.

Randee Wismer is a 2023 graduate of Drexel University’s English program. She spent her college career involved with non-profits and is especially interested in just outcomes for justice-involved people. She currently works with the Philadelphia Lawyers for Social Equity.