In Everywhere I Look, Ona Gritz confronts one of the most agonizing questions a person can face: How do we come to know someone who is already gone, especially when we never truly understood them in life? Through a blend of elegy, investigative memoir, and quiet reckoning, Gritz resurrects the memory of her adoptive sister, Angie, whose brutal murder in 1982 marked an irreversible fracture in the author’s world. But this is not a true crime book; it is not even primarily about the murder. Instead, Everywhere I Look is a work of haunting emotional archaeology–an effort to piece together Angie’s life, personality, and pain from the remnants left behind. In doing so, Gritz also reconstructs herself, coming to terms with childhood favoritism, family dysfunction, and survivor’s guilt.

The book is written as a letter to Angie, who died alongside her husband, infant son, and unborn child in an unthinkable act of violence perpetrated by two drifters they had taken into their home in San Francisco. Gritz was a college sophomore at the time, and her initial reaction—emotional paralysis—sets the tone for decades of silence and buried grief. Now, years later, she opens that sealed vault of feeling with precision and vulnerability.

Rather than proceed chronologically, Gritz organizes her narrative in a lyrical, fragmentary style that mirrors the nature of memory and trauma. The book moves between timelines, juxtaposing the present-day search for information about Angie with flashbacks to their childhood. We learn that while Gritz, who was born with cerebral palsy, was often seen as the fragile one in the family, Angie was cast as the rebel, the problem, the “black sheep.” The irony, of course, is that Angie—the able-bodied child—was the one shuffled between institutions, sent away for perceived behavioral issues, and ultimately left unsupported by a family that seemed unwilling or unable to understand her.

Gritz’s choice to write the memoir as directly addressing Angie allows for an intimate tone throughout. She speaks to her sister not just as a grieving sibling, but as a woman looking for reconciliation across time. The voice is restrained but emotionally charged, carrying the weight of regret and longing without tipping into sentimentality. “I should have asked more questions,” she says over and over, in various forms. That theme of missed chances for understanding echoes throughout the book, particularly in Gritz’s belated discovery of Angie’s traumatic institutional history. Through school records, court documents, and interviews, Gritz learns that Angie endured years of mistreatment that no one in the family, including Ona herself, seemed to know or acknowledge at the time.

Yet the memoir resists flattening Angie into a figure of pure tragedy. One of its great strengths is its portrayal of Angie as complex and real. She was someone who painted her nails dramatically, who fought with their mother, who yearned for connection even as she pushed people away. She made choices—some dangerous, some generous—that reveal a fuller portrait of a woman trying to build a life despite never having been offered the scaffolding most of us take for granted in our childhood.

In exploring Angie’s life, Gritz is forced to confront the privileged position she held within the family. While both sisters were “different” in their own ways—Gritz due to disability, Angie due to behavior—only one was protected, nurtured, and believed. The memoir is sharply self-aware in this regard, unafraid to scrutinize the dynamics of favoritism and internalized ableism. Gritz’s reflections are all the more powerful for their honesty. She neither exonerates nor condemns herself, but sits with the discomfort of her position.

Stylistically, the memoir is understated and poetic. Gritz, who is also a poet and children’s author, brings careful attention to language that elevates even the smallest details into moments of resonance. These sensory fragments help the reader to feel Angie’s presence even as we share Gritz’s sorrow at her absence: “Heart pounding, I leapt off the bed and began pacing, my lethargy melted by a clear, hot sense of purpose.”

What ultimately makes Everywhere I Look so compelling is its refusal to offer neat closure. There are no tidy resolutions or full understanding to be reached. This is how life is. What Gritz achieves, instead, is an ethical and emotional excavation—a re-centering of Angie not just as a victim of violence, but as a person who mattered, who was loved, and who deserves to be remembered not for how she died, but for how she lived. The memoir itself becomes a monument of words, questions, and the kind of love that tries to see someone in their entirety.

Everywhere I Look is not a loud book, but it is an essential one. It speaks to the ways we live alongside mystery and grief, and how the act of writing can become an act of both mourning and reclamation. With extraordinary compassion and craft, Ona Gritz ensures that her sister will not be forgotten—not just as a story, but as a person.

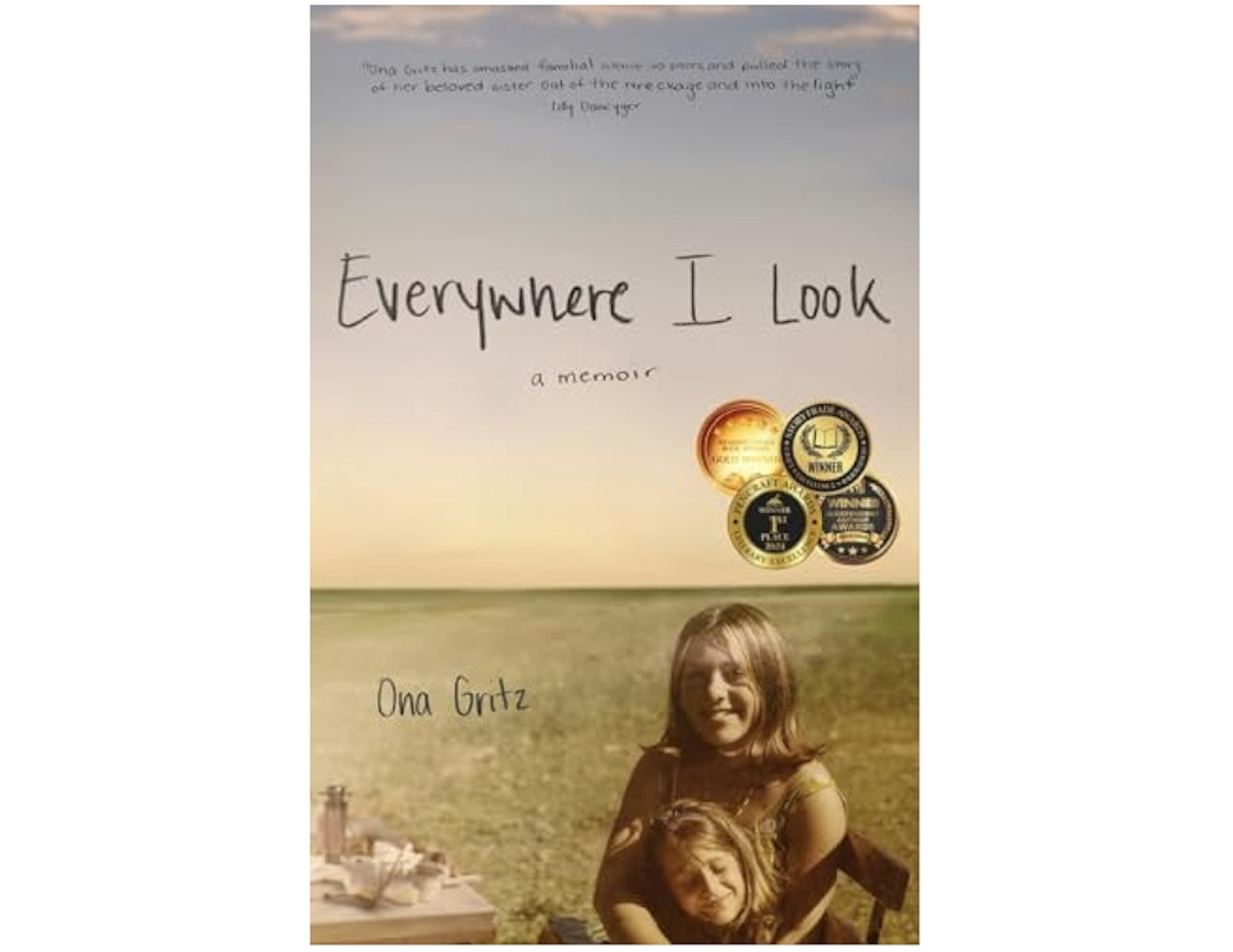

Everywhere I Look

Ona Gritz

Apprentice House Press

April 16, 2024

237 pages

Harper Lower is a second-year student at Drexel University majoring in English with a concentration in Writing. She loves to read and write short stories in her free time.