The beauty and tragedy of Alan Turing … the brilliance and difference of his mind and spirit, right from childhood … the sorrow and dedication of his mother, Sara, as she reads over his archives while preparing a biography of her son … the opening out of new poetries thanks to his original mind … life in our present world of unblinking screens, a world here thanks largely to Turing … all this and more resonates in Philadelphian poet Leah Falk’s to look after and use.

Born in London, Turing (1912-1954) forged huge, permanent innovations in mathematics, philosophy, computer science, electrical engineering, and even biology. He is renowned for his cryptanalysis work during the Second World War, during which, at the Bletchley Park codebreaking complex, he was a driving force in cracking Enigma, the German coding system then regarded as unbreakable. (See the somewhat fanciful film The Imitation Game, starring Benedict Cumberbatch.)

Credited with shortening the war and saving many lives, his work led eventually to the development of artificial intelligence and digital computing. Among many other accomplishments, he was also a world-class long-distance runner. All these facets of him flicker through to look after and to use.

The title comes from 16-year-old Turing’s remark that “the body is something for the spirit to look after and use.” (On top of everything else, he seems, at least as a young man, to have had a mystical streak.) And the center of the book is his mother Sara’s struggle to understand him through his writings and drawings as she prepares the biography after his death at age 41.

Let’s applaud Falk for her brilliant ways of embodying difficult moral, psychological, and mathematical issues. I really admire the sinuousness of her poetry, her wondrous use of white space, the constant explosion of lovely moments.

Parents and children are the emotional core of to look after and use. As the soul looks after the body, parents look after their children. Falk even addresses a poem, “Out and Back,” to her own father, in echoes of the Sara/Alan connection:

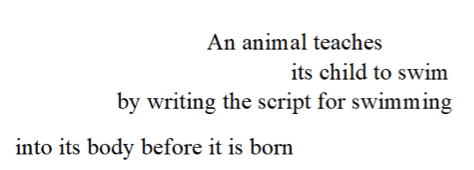

“Evidence of the Making Process” touches on Turing’s fascination (well before the discovery of the double-helix in DNA) with how life-instructions are encoded in living machines, which pass them on (as biological “hardware”) to their offspring; these instructions, he saw, also enable parents to teach (as “software”) those offspring:

Later in the poem, this repeats in a simpler, more expansive form.

This intense, condensed little book is a novel of a sort, told in discontinuous yet emotionally consecutive poems. That’s how poetry often tells stories best: in moments, images, epiphanies, bursts and complexes of realization and confounded ecstasy. The gaps are eloquent on their own behalf, inviting us to run with all the possibilities and connections.

Sara Turing is the heartbreaking center. We read her reading Alan reading the world. In “Précis of Einstein’s Theory of Relativity,” she ponders her teenage son’s essay explaining the theory to her. She’s reading hard, very hard, “so that somehow./ like two straight lines/ we can move past each other.” She watches his handwriting change as he grows up, ending in loops that “begin to sound/ something like round, something like/ what was once the one world.” Whispered — what a lullaby of initial w- sounds! — in that last sad, exquisite line is her effort to retrieve, to restore wholeness to a broken universe.

Here is “Annotation, Sara Turing, 1954”:

The title year is the year Turing died, two years after he was convicted of homosexuality and “agreed to” (the horrifying phrase used in many accounts) chemical castration via stilbestrol.

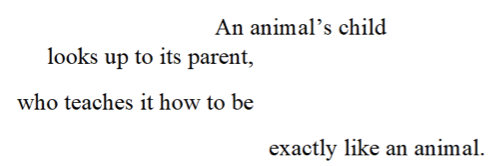

His death was ruled a suicide by ingestion of cyanide. Like much about Turing, this remains controversial since, some say, the evidence was also consistent with accidental ingestion. Let’s imagine this poem as coming from Sara’s viewpoint. Perhaps she is resisting “the verdict// about the mouth,” presumably the scent of bitter almonds suggesting cyanide. But rather than almonds we find accident, as if, via that switch of words that somewhat share an initial a- sound, Sara is defying the ruling.

A “bitter// accident” indeed. Blank space intervenes, as, perhaps, she muses that her son’s mind was in a perilous “balance,” declared in the italicized sentence, from a 1952 letter to his friend and fellow mathematician Norman Routledge, in which Turing lays out what he’s about to be convicted of, signing off with “Yours in distress, Alan.” (Not quoted here, but if you know the letter, as Sara does, it hurts more. The letter becomes the subject of a later poem.)

And then a very long pause.

In that gap, it’s easy to imagine Sara thinking, perhaps, that if Alan had been unable to concentrate because of his heinous fate, if that beautiful mind had been distracted and distressed, his death might well have been an accident.

After another long pause, the poem ends with what “Others always thought” and what “Alan always knew.” Maybe Sara rounds back to the furious tyranny of social judgment versus Alan’s self-knowledge.

That’s what saves this from being a grieving mother’s special pleading. She ends where, in a sense, she begins. Social judgment, the enforcement machine’s rush to punishment, lay behind the “verdict” of suicide. As in “Of course he did; he was a deviant.” Punishing the dead.

Falk’s poem superlatively enacts a critical juncture in the story of mother and son, never more beautifully than in the eloquent gaps.

“The Impossible Problem” involves Gödel’s Theorem, positing that systems of numerical problem-solving cannot be both complete and consistent. There are limits to what can be decided about these systems from within the systems themselves. Turing’s first great contribution to mathematics was to approach this theorem by imagining computing machines, now known as Turing machines, that work by algorithms. Falk makes agile imaginative work of all this:

This exhilarating rush of images shows us seeds, rivers, ceramics, swimming, natural and human activities that cannot be either proved (they don’t require proof; they just are) or disproved (they can’t be; they just are). Something about existence — or, better, our systems for making sense of existence — fail before the fact of existence itself. Notice that where “Annotation, Sara Turing, 1954” is nearly devoid of images, “The Impossible Problem” is a cavalcade of them, bodying forth the problem.

Are we continuous? Are we ever complete? (“There is nothing better,/ I assure you/ than to be complete.”) to look after and use is Leah Falk’s masterful encounter with a man’s great mind and greater suffering, bequeathed in writing to a mother who wrote him. Such vibrant work chimes with one of the best, most resonant, most joyful utterances in this book: “The machine’s behavior” — the machine we are and the machine we make, child, poem, computer — “is play.”

to look after and use

By Leah Falk

Finishing Line Press

Published on September 18, 2019

46 pages

John Timpane, the former Books Editor and Theater Critic for the Philadelphia Inquirer, is a retired English teacher and journalist living and working in New Jersey. His work has appeared in Sequoia, North of Oxford, Apiary, Painted Bride Quarterly, Schuylkill Valley Journal, Per Contra, Vocabula Review, Truthdig, and elsewhere. His latest book, a chapbook, is Buck in the Piano Room (Philadelphia: Moonstone Press).