Rich Westcott, one of the leading experts on the history of baseball in Philadelphia tackles two important but understudied topics in his latest book, Biz Mackey, A Giant Behind the Plate. Not only does Westcott offer the first book-length biography of Biz Mackey, a Hall of Fame catcher who played his entire career in the segregated Negro Leagues and spent his best years in Philadelphia, but he also provides readers with a succinct history of African American baseball in Philadelphia.

Westcott starts by using the voices of Mackey’s contemporaries and scholars of the game to explain how good Mackey was. As many casual baseball fans may not have heard of Mackey, this section is vital. He then moves into a chronological examination of Mackey’s life beginning with this childhood in Texas, moving through his different stops in professional baseball, and ending with his posthumous induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York in 2006. Westcott intersperses topical chapters examining the history of black baseball in Philadelphia and Mackey’s powerful influence on another Hall of Fame African American catcher, Philadelphia native Roy Campanella, into his narrative.

Mackey began his professional career in his native Texas in 1918 before moving to the Indianapolis ABCs of the brand-new Negro National League in 1920. Mackey excelled with the ABCs before moving to the Hilldale Daises in 1923, a team in the then-new Eastern Colored League that played their home games just outside of Philadelphia in Yeadon, Pennsylvania. With the Daises, Mackey played in the first ever Negro World Series in 1924 and won the title in 1925. Negro League observers widely considered him the best defensive catcher in the league, and he was also a force at the plate, winning the league batting title in 1923. Mackey continued to play with the Daises until 1932. The next year, he joined the Philadelphia Stars, a new team, and the following year the Stars won the Negro National League title. Following their title run, the Stars fell off the pace of the best teams in the league and Mackey, then in his late 30s, saw his skills begin to decline. Eventually the Stars traded Mackey to the Elite Giants, then based in Columbus, Ohio, but soon to relocate to Baltimore.

With the Elite Giants, Mackey became a player-manager, another position in which he excelled. Westcott argues that not only was Mackey willing to teach and mentor younger players on the finer points of the game—a rarity for a player of his caliber according to Westcott—but that he was exceptionally talented at helping those players develop their skills. He was so good at this, as Westcott claims, that the team no longer had a need for him because he had trained Campanella so well that his own talents became superfluous. Mackey soon found another managerial position with the Newark Eagles where he mentored future Hall of Famers Monte Irvin and Larry Doby as well as star pitcher Don Newcombe. Mackey led the Eagles to the 1946 Negro World Series title, the last Negro League championship played before Jackie Robinson integrated Major League Baseball.

Some of the most interesting aspects of Mackey’s life were his repeated exhibition tours of Japan in the 1920s and 1930s. Mackey made his first trip to Japan in 1927 where he and a team of Negro Leaguers played against Japanese teams and impressed players and fans alike with their skills. Mackey returned on exhibition tours in 1932 and 1935 and each time his team won nearly all of their games. Westcott, backed by the interpretations of several scholars of Japanese baseball history, argues that Mackey, who met Emperor Hirohito in Japan, was instrumental in the development and increasing popularity of baseball in that country. Westcott also claims that even though Mackey’s teams were far superior to their competition, in a country where he and his teammates were treated as equals despite the color of their skin, they always treated their Japanese opponents with the utmost respect, in contrast to the way traveling major league players behaved there.

Despite the difficulty of researching the life of a person like Mackey who left few records and whose exploits were mostly only covered in weekly, black-owned newspapers, Westcott would have been well-served to avoid contradicting himself. For example, Westcott offers different batting averages for Mackey’s stellar 1923 season at different points in the book and at one point claims that Mackey and his future wife, Lucille, met on Mackey’s first trip to Japan while at another point claims it was on his third trip there. Westcott also quotes Mackey discussing living with his wife in the Los Angeles area in 1942 in one chapter, but in another says she was still living in Japan during World War II and that the couple had lost touch only to be reunited after the war. That said, Biz Mackey, A Giant Behind the Plate is a vital contribution to the history of baseball in Philadelphia, the nation, and across the globe.

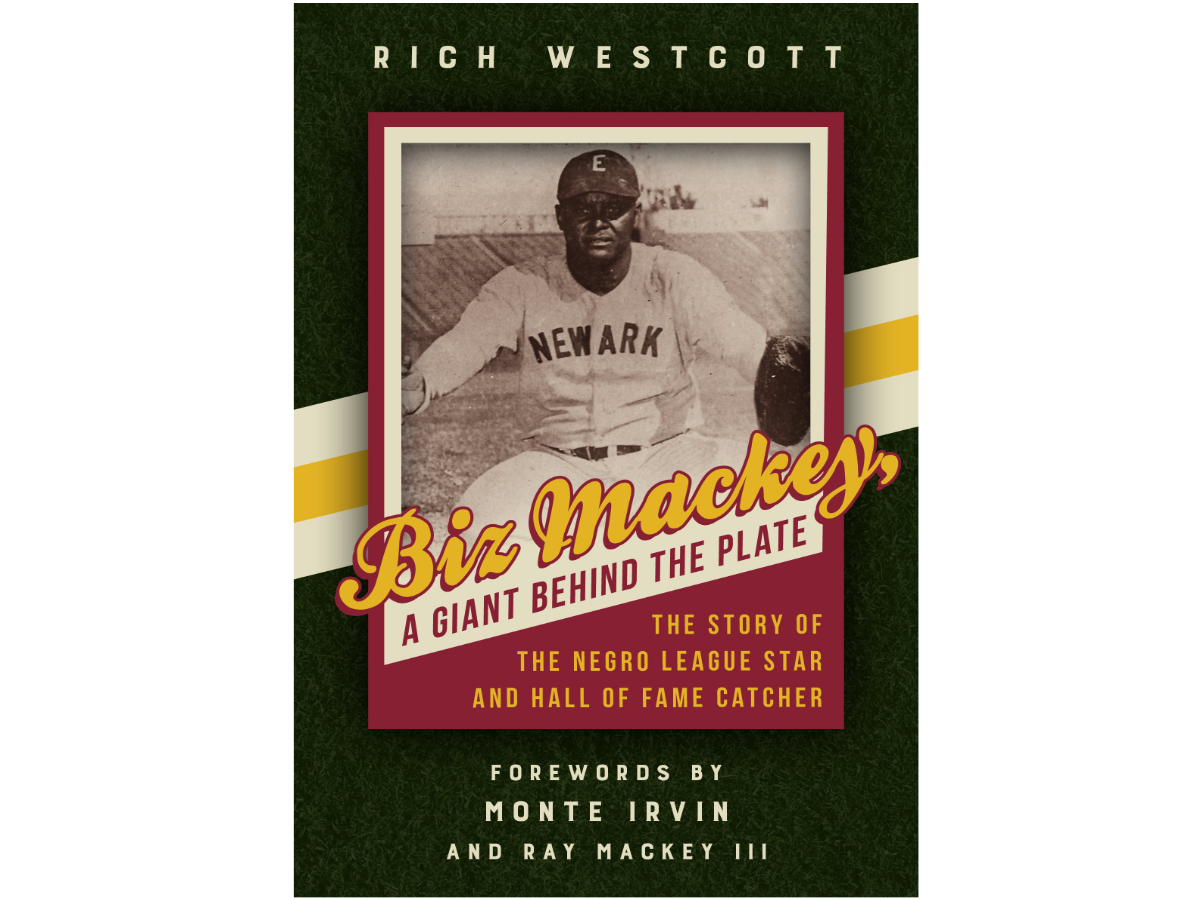

Biz Mackey, a Giant behind the Plate: The Story of the Negro League Star and Hall of Fame Catcher

By Rich Westcott

Temple University Press

Published on February 1, 2018. New in paperback for 2020.

208 Pages

Seth S. Tannenbaum is Visiting Scholar and Adjunct Professor in the Department of History at Drexel University. He is a lifelong Philadelphian who earned his Ph.D. in history at Temple University. His manuscript in progress is titled Ballparks as America: The Fan Experience at Major League Baseball Parks in the Twentieth Century. His work has appeared in the Washington Post, Sport in American History, and a number of edited volumes and academic journals. Seth can be found on twitter @SethSTannenbaum.