Ed Ruggero’s Blame the Dead takes place during the Allied invasion of Sicily in August of 1943, an event that is often overshadowed in the popular imagination by the D-Day assault. This historical mystery welds together the trope of rogue cop (the justice-giver who challenges institutional rot) with a portrait of the human toll of invasion.

Blame The Dead feels authentic perhaps because Ruggero brings firsthand experience to his writing. A West Point graduate and an army officer, Ruggero has written several novels with a military backdrop (Breaking Ranks and 38 North Yankee) and nonfiction about military history (The First Men in: US Paratroopers and the Fight to Save D-Day). In Blame The Dead, Ruggero does not sentimentalize wars or the men who fight in them. The novel is good at convincing the reader that the invasion of Italy was a messy affair, emphasizing the chaos and the breakdown of any sort of military discipline. “Every roadside was littered with discarded ration cans and cigarette packs, fire-blackened German and Italian war equipment, bloody bandages, used condoms, splintered furniture, filthy clothing, dead burros, and the occasional unburied enemy soldier, bloated and black and stripped of his shoes.”

The novel opens on the murder of a surgeon who is part of a field hospital that cares for the human fallout from the invasion. Enter, by chance, Eddie Harkins, a hot-tempered Irishman from Kensington, a former beat cop who dropped out of Villanova, now an MP who is passing by. (Local readers will enjoy the occasional references to Philadelphia.) Harkins is ordered into the detective role because there is simply no one else available.

The hospital setting reverses the Mash premise of military doctors as unsung heroes, pointing to, in particular, the murder victim’s sexual harassment—to the point of rape—of the serving nurses and the general acceptance of this behavior by most of the doctors and officers. Oddly enough, the one doctor who puts patients above his own interests is a German prisoner of war, a urologist. This character’s specialty allows the author to insert lots of material that underscores the importance of the penis to the men. Ultimately, from the novel’s viewpoint, it is generally nurses, not doctors, who are the real heroes of the unit.

Blame the Dead starts off slowly and only really starts to engage the reader when the invasion becomes mere occasion and the pursuit of the murderer begins. At that point, the military becomes just one more large institution that hopes to cover up its failures—just as the institutional structure of the police or the government sometimes functions in mysteries.

Once the invasion becomes merely chaotic backdrop—in the manner of the trope of the corrupt city—the plot is driven by Harkins’ character. As an MP, Harkins is an outsider whose many quick-fisted responses are explained through references to his brawling Uncle Jimmy who lived in “his own black-and-white world” and never had “any second thoughts about his behavior, unless it was to figure out how to hand out a more effective beating.” If the reader is comfortable with the characterization of Harkins—complete with a large close-knit family (Harkins’ brother, a brawny priest paratrooper, just happens to land in Palermo to be on hand to give mellowing advice and confession to Harkins)—and a love interest, Kathleen Donnelly, who also is from the old neighborhood, the novel works well. For me, Harkins as moral center was sometimes off-putting. In order to make the modern premise of harassment work in the 1943 context, Harkin’s angry response to the behavior has to be explained as a matter of familial/local propriety. Harkins explains: “[I]f one of his sisters had come home telling this story, he and his brothers would have raced each other out the door to teach the guy some manners.” Later, Harkins recounts how, as a young cop, he was part of his fellow officers’ decision to push the rapist of a young girl off a roof.

While the main character in mysteries is often at odds with authority and the reigning order, Harkins seems to be rubbed wrong by virtually everyone (who isn’t family or from the old neighborhood) he meets. Perhaps one insight into Harkins’ nature can be found in his reaction to the German POWs: their formality, being so “by the book,” makes him want to “cuss and slouch and act like a slob.” The sole exception to Harkins’ general disdain is the first sergeant of the unit (a non-com). Drawn as a Wallace-Beeryesque character, Drake is old school army who puts the unit first. This reader wondered why Harkins takes winning Drake’s grudging respect as such a personal challenge.

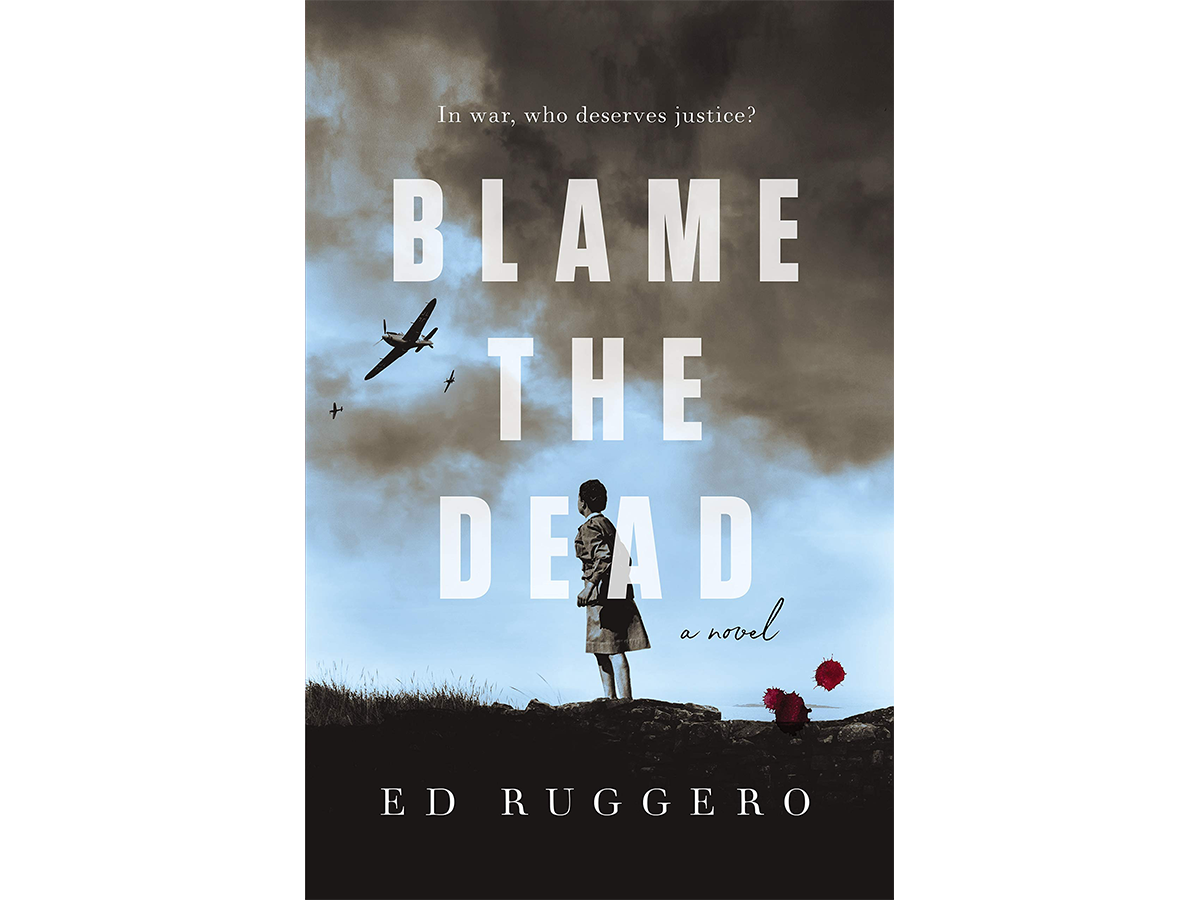

All in all, Blame the Dead is a reasonably good read for the long hours of an airplane flight. Yet when one of the several versions of the book cover images proclaims, “Who deserves justice?”, we may want to ask in whose hands do we place that decision?

Blame The Dead

by Ed Ruggero

Forge Books

Published on March 3, 2020

336 Pages

Doreen Alvarez Saar is Professor of English at Drexel University and the American Literature (to 1865) Editor of the Rocky Mountain Review of Language and Literature.