A beguiling experience, Kacen Callender’s Queen of the Conquered is at one and the same time a vacation on a tropical island, a voyage confronting the historical experience of slavery, and a delicate and nuanced exploration of the contemporary issue of what it may mean to be “woke.” Best of all, it is an engrossing story which sucks the reader into solving a central mystery: who is murdering the leaders of the government of Hans Lollik, a fictional country clearly modeled on the Caribbean’s Virgin Islands?

When I lived on St. Thomas, there were many clear days when we could, by standing on the porch of our house, see the small island of Hans Lollik on the horizon just beyond the sand-rimmed blue disk of Megan’s Bay. In Queen of the Conquered, the name Hans Lollik has, by synecdoche, been transferred to an imaginary nineteenth-century country overseen by a Danish regent, but readers will recognize the landscape and history of the American Paradise.

Sigourney Rose, Callender’s protagonist, is the only free black woman among the otherwise fair-skinned nobility of Hans Lollik. She is invited, with the other nobles, to spend the storm season on the regent’s island sanctuary, but her own plans involve wreaking revenge on the nobles who conspired to murder her family years ago, an exceptionally difficult task in a fantasy world where most of the nobles, and some of the islanders, are endowed with superhuman psychic powers. However, Sigourney seems not to be the only noble with a murderous plot to execute. The king has announced plans to retire, and the nobles taking refuge from storm season are jockeying to take his place.

When is a refuge not a refuge? Why, when those around you succumb to, or narrowly escape, machinations whose aim seems to include causing your execution by making you their scapegoat. In fact, “goat in a white dress” is how the other nobles describe our hero who, unfortunately for her enemies, can read their thoughts. She must use her psychic powers to figure out the plans of the plotters before she is fatally entangled in their schemes.

Along with her aim of revenge, Sigourney entertains the dream of becoming the regent and improving the lot of the enslaved islanders. She hopes to accomplish her goal though she realizes she disgusts her fellow nobles because of her skin color. She looks like their slaves but is, by the accident of her birth, a free woman and the member of a noble family. The nobles of Danish ancestry would like to put her back into what they view as her place. And yet Callender’s protagonist is a flawed hero. She has inherited her estate from her mother, whose intention was to free all her slaves at her death, but she manumits only one, rationalizing that freeing them all would interfere with avenging her mother’s death. As a result, as she moves about Hans Lollik, Sigourney constantly encounters the hatred of both her own household workers and other enslaved islanders.

Slavery cuts deep and long. When we lived above Megan’s Bay, we inhabited a culture and a commercial world that seemed, refreshingly to us, owned and managed by the islanders, but the social structure was not as simple as we thought. Now I belong to a Facebook group designed to keep tourists focused on the fantasy islands they visit from time to time. Underwater pictures and recommendations for charter boats abound; political discussion is frowned on. When real islanders, mostly people of color, occasionally volunteer comments about the ways that tourism is transforming their home into a place they can’t afford, they are quickly reminded that the group is not the place for such a discussion.

Callender (preferred pronoun “they”) is a person of color raised in the islands, so they know well the ways that a history of slavery can warp the moral fabric of a society. Sigourney realizes that her fellow nobles are afflicted with the inevitable taint that attends turning a human being into an object that can be bought and sold. Here is what she sees in the mind of the most sympathetic of her fellows:

Yes that’s the secret to Beate Larsen, I realize—she’s filled with so much love. Beate Larsen believes me beneath her, in the way that a human being might think the goat beneath them, incapable of true thought and feeling. But still she tells herself that she loves me in the way that a child might begin to love and care for that goat, playing games with one another, until finally the goat is slaughtered. She sees the pain of my people and wonders if it can be right for the Fjern [the nobles] to treat us the way that they do. She prays for all of our souls, islanders and Fjern together, and hopes that the gods may forgive the sins of her people. But still, this is all that she will do.

Queen of the Conquered shows that being “woke” cannot just consist of sympathy and kindness; it requires the active dismantling of the social structure that permits slavery, a process still going on in the Virgin Islands. That is the ultimate challenge that Sigourney faces in the picturesque but brutal world of this entertaining and thought-provoking novel.

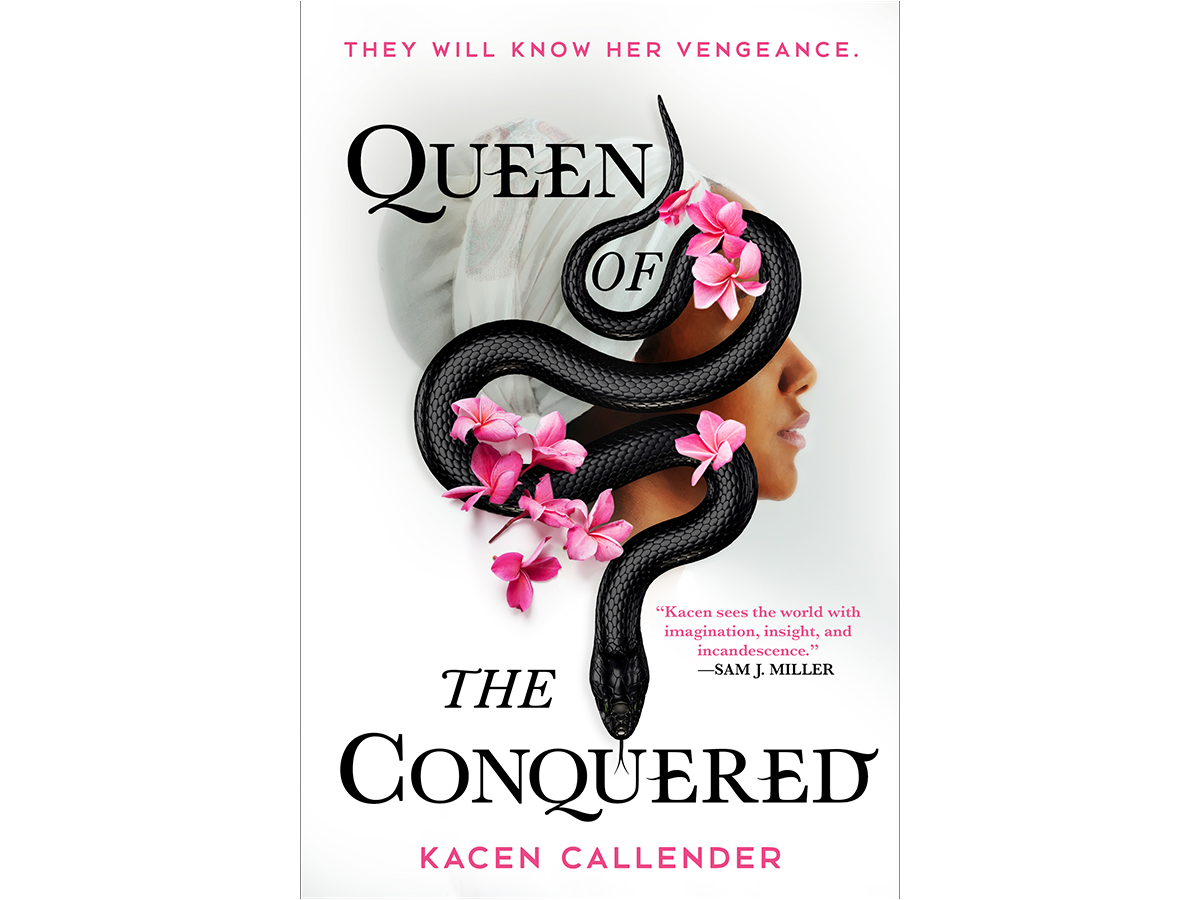

Queen of the Conquered

by Kacen Callender

Orbit

Published on November 12, 2019

400 pages

Eva Thury teaches in the Department of English and Philosophy at Drexel University in Philadelphia. She once described herself on PBS rather grandiosely as having “a black belt in mythology” as a result of co-writing Introduction to Mythology Contemporary Approaches to Classical and World Myths, 4th ed. (Oxford 2016) with Margaret K. Devinney. She is also the translator from the Hungarian of Sándor Bacskai’s One Step toward Jerusalem: Oral Histories of Orthodox Jews in Stalinist Hungary. Though trained as a classicist, Thury sees herself as a student of popular culture, pursuing interests in everything from vampires to Sandy Skoglund’s radioactive cats.