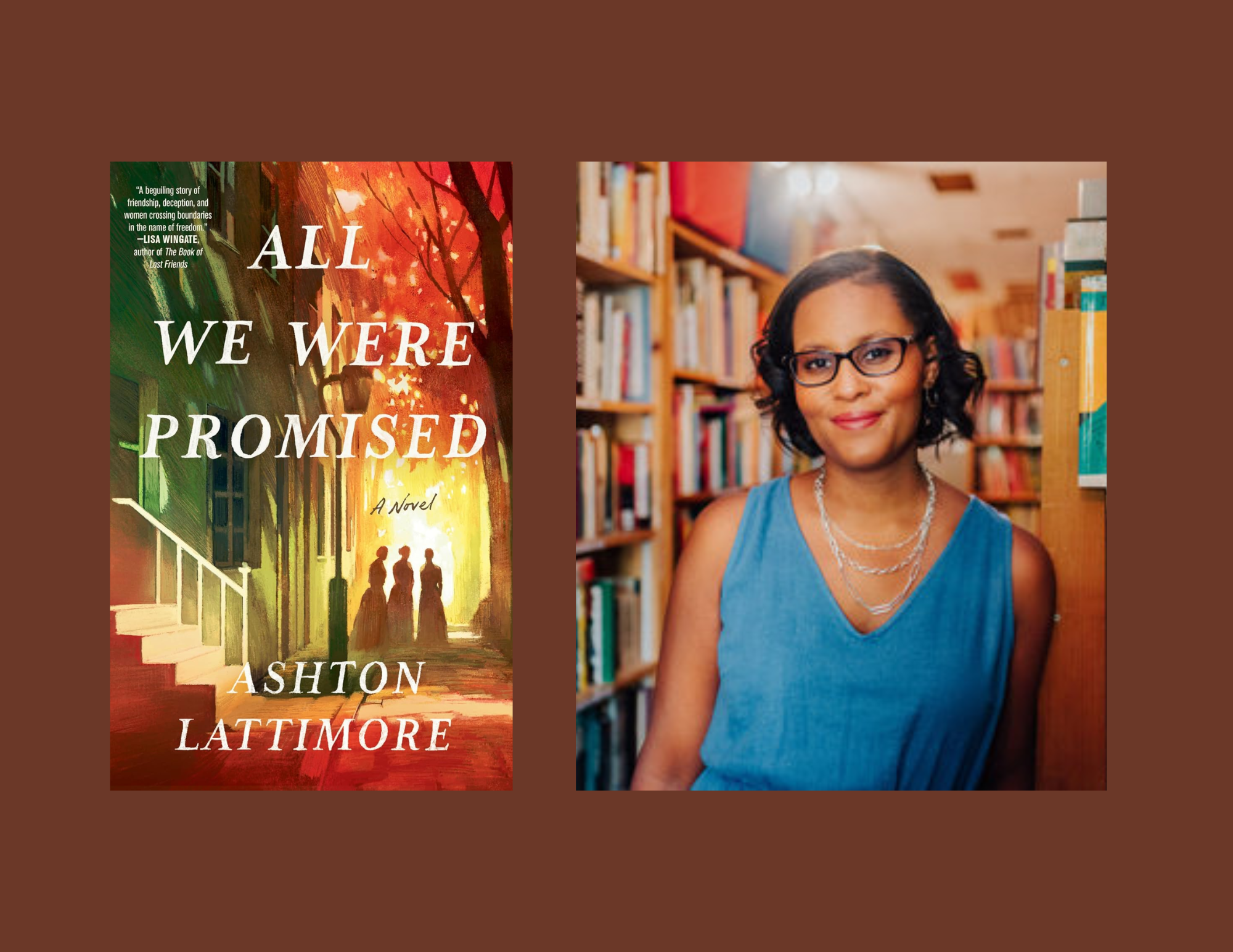

Ashton Lattimore is an author, award winning journalist, and former lawyer. Her debut novel, All We Were Promised, follows the lives of three young Black women in pre-Civil War Philadelphia. Lattimore resides in suburban Philadelphia with her husband and two sons.

Mia Rheineck: When did you begin writing and viewing writing as a career path?

Ashton Lattimore: I started writing probably when I was nine or ten. It was when my family first got a computer. I realized very quickly that I could go into WordPerfect (this was before Microsoft Word) and type out stories and print them out and make people read them, so that’ is what I did.

MR: When did you start viewing writing as a career path?

AL: I started thinking of it as a career path in college, when I started doing journalism and writing for the school newspaper. I formed a plan to go into journalism after college was over and that’s what I did. As far as fiction writing, that’s more recent. I started writing All We Were Promised in 2018. It was the first fiction I’d ever written, so that was the first time I had thought of fiction writing as potentially being a career path.

MR: How was it switching from journalism writing to writing a novel?

AL: I think I carried over a lot of practices, especially research and fact-checking practices, from journalism with me. Since I’m writing historical fiction, accuracy is really important, whether it’ is a type of dress that someone would’ve worn or what kind of wood someone might have used to make a dresser or a table. I think it’s just been an exercise in learning to not fear the freedom that comes with fiction writing. There are constraints, but a lot of it is just made up. I can just have the characters do whatever I say they do, and I’ve had to figure out how to not be intimidated and overwhelmed by that degree of freedom because journalism doesn’t necessarily give you that.

MR: Did anything from your experience as a lawyer play a part in writing a novel?

AL: I think the research and fact checking are similar. The other piece of it is in the stories I choose to tell. I’m often drawn to stories that have a legal component to them. With All We Were Promised there’s this six-month law and the laws around emancipation in Pennsylvania that I found really interesting and wove into the story. The next thing that I’m working on deals with Prohibition, which is its own set of legal restrictions.

MR: What inspired you to write All We Were Promised?

AL: It was a mix of a couple of things. I was working in Philadelphia at the time I started writing All We Were Promised. I would sometimes go visit historical sites on my lunch break or just when I had time and at one of those historical sites, the President’s House, I learned about people basically trying to cycle their enslaved people in and out of the state for a period of time to prevent them from establishing enough residency to be free. That’s one of the things I built this story around. The other piece of it was the characters, which initially came to me as an idea based on a musical. I really am a big Broadway nerd, so Les Misérables is the inspiration for several of the characters in All We Were Promised. I was listening to the soundtrack of Les Mis one day at work and was just struck with this idea to take the story and transplant it to the United States. These characters all have analogs that go back to Les Mis. The main ones are Jean Valjean, Cosette, Eponine, Javert, and Marius. Those main characters all appear in some form, changed a lot. The structure of someone leaving a place and being chased down by the thing that they left helped me shape the story that ultimately turned into the book.

MR: Why was it important to you to write a novel focused on three women and all of them having agency at some point?

AL: I felt like it was important because the way that a lot of us are taught the history of women, taught the history of enslaved people, even the way that we are taught the history of the abolitionist movement is very much something that was done to and for black people by benevolent white abolitionists who let them stay in their homes and who helped advocate for them politically. For me to dig into the research and learn how politically active women were, how they used their voices, how they opened up their homes to other black people and it wasn’t necessarily this, there were certainly cross-racial coalitions, they did exist, but that’s not what the vast majority of the Underground Railroad really was. I felt I wanted to share with the rest of the world.

MR: What was the writing process like for this? Were you often writing from historical sites, archives?

AL: I started with research. The idea came to me in October of 2018, so I started learning about Pennsylvania history, figuring out which time period I want to set the story in. I was working at the University of Pennsylvania at the time, so I had access to their library which was very handy. I started diving into research to make sure that I understood the period and if there were any major historical events that I wanted to include in this story and that’s how I learned about Pennsylvania Hall and the fire that destroyed it. I decided to build the story around that. Then in November, just writing any little scrap of time that I got and trying to reshape and finish the story over the next three or four years. It ended up taking from 2018 to 2022, when I ultimately got the deal to get it published.

MR: How did the pandemic affect your process for this novel?

AL: During the pandemic, I was still very much in the writing phase. It was hard because my husband and I moved out to York, Pennsylvania which is central Pennsylvania, to stay with my in-laws, so we were all kind of a pod at that point. I didn’t have my books with me a lot of the time for the research. I ended up doing a lot more online at that point. I couldn’t go walk around Philadelphia, so I had to rely on Google Maps to remember what certain streets look like, like Streetview and kind of work from that. I still had the research I had done before and I had walked around Philadelphia plenty of times prior to that so I still had those memories. But for little specific things, like what does this little backstreet look like? It was just me in Google Steetview.

MR: I read an article saying the story changed quite a bit from what it initially was going to be to what it ended up becoming. Can you elaborate on that? Were the changes from something you did not like in the writing or was it a publisher/editor comment?

AL: It was just me. It initially started as two points of view, Charlotte and her father (James) and it went back and forth between the two of them. As I was writing it, I found that her father’s story, because part of what he is doing is he is passing for white, the story was just taking me places I didn’t really want to go or didn’t really find that interesting. As I’m writing Charlotte’s chapters, other characters like Nell and Evie are showing up and tempting me towards worlds I had never seen before in a published book. Nell is this wealthy abolitionist, she is sort of a socialite. She is this free black woman thirty years before the civil war who’s never been enslaved, her parents have never been enslaved, she doesn’t worry about money or really worry about much of anything. That’s just not a world I had seen somewhere before, so I just started feeling as I am writing Charlotte’s chapters, and I see Nell go off somewhere, I want to go with her, I want to go see what she’s doing and really feeling that draw towards her point of view. At the same time, I’m feeling like Evie as an enslaved young girl deserved to have pride of place in the story because it’s her story of how she gets free. So, treating her as a plot point in somebody else’s chapters started to feel very strange. When I made the decision to reshape the story, it just felt a lot more like the story I wanted to tell. I ended up finding ways to subsume James’ story into Charlotte’s chapters and ended up feeling like I made the right call.

MR: Are there historical details from the book that you have found audiences are maybe surprised by or react to?

AL: Definitely the six-month rule. People are usually surprised to learn that George Washington engaged in this behavior. I think the other piece is just Nell’s whole world, I think people are very surprised to learn that there were these free black people, like generations of free black people, who were wealthy, middle-class, upper-class and had this very sophisticated political and social life at this time when that is just not our understanding of what life was like for black people at that time. The other piece of it is the catering, with the Merion family running these catering businesses because that’s a piece of true history as well. And Pennsylvania Hall. Nobody knows about Pennsylvania Hall. That’s usually brand-new news to people, and to learn that it only stood for three or four days before it was burnt down is usually surprising.

MR: I did see you are writing a new book. Is there anything you can share about that?

AL: I think I better keep quiet about it for now, but hopefully more to come soon!

Learn more about Ashton Lattimore on her website here and order All We Were Promised here.

Mia Rheineck is a fifth-year student at Drexel University majoring in English and Global Studies and minoring in Middle Eastern and North African Studies. She loves to use writing and reading to explore new topics and ideas. Outside of school, Mia enjoys sports, reading, and being outside.