The first thing to tell you is that these are not fairytales for children. Christina Rosso’s She is a Beast bristles with angry women, maidens who have been wronged for too long but who are far from helpless. The Prologue says “The women in this book answer to no man, or creature; they are their own keepers. Don’t be fooled by their beauty or supposed innocence. Their teeth are sharp as daggers…”

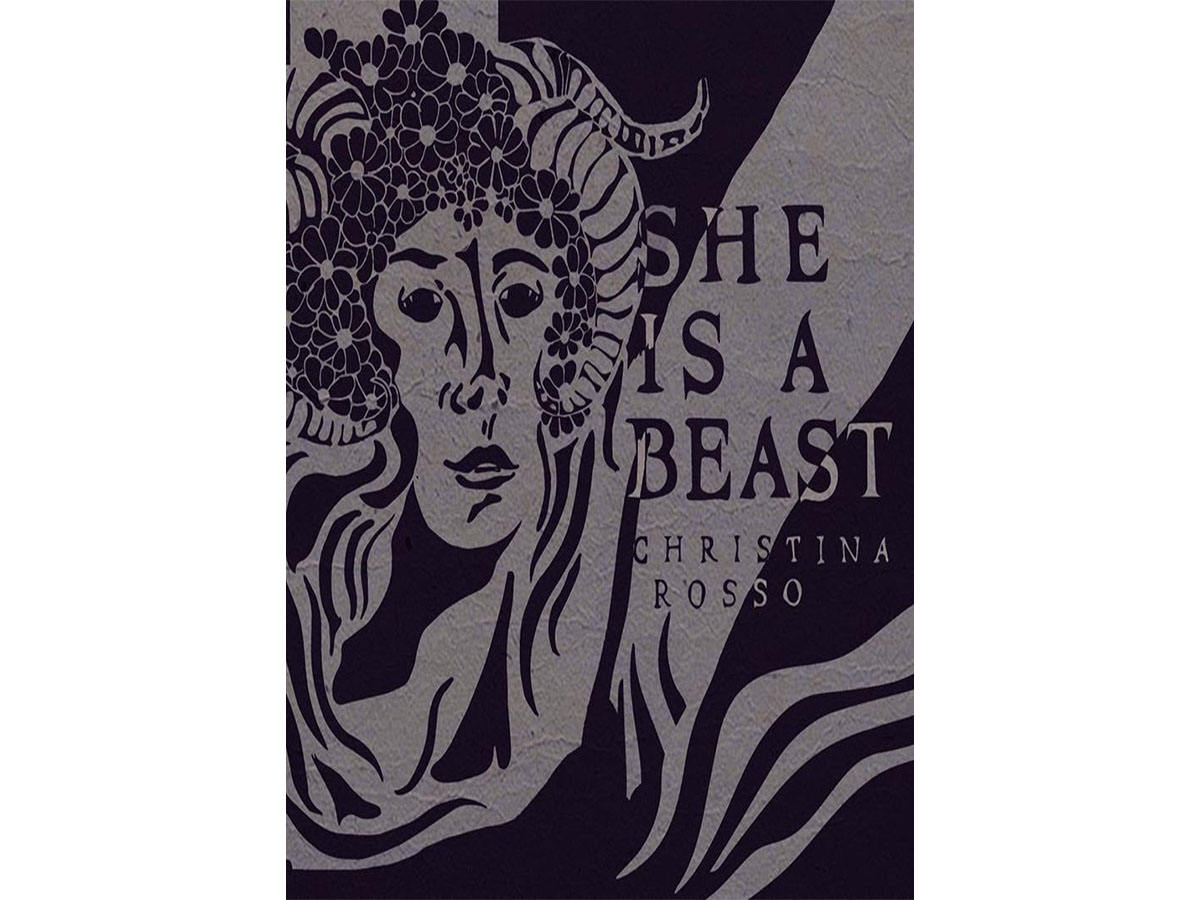

Also, She is a Beast is a beautiful book, elegantly laid out and illustrated in a sly and magical fashion by Jeremy Gaulke. My favorite picture is of Cinderella scrubbing the floor with books and a glass of water on her head, devices for ensuring her carriage is not stunted by the household drudgery she is forced to endure. I am also very fond of the magical hedge warning suitors away from Briar Rose, an intricate three-page construction that keeps the sleeping princess safe because, as she says, “You don’t want to wake me up. Because if you do, you’ll learn real quick that I don’t match up to your image of me. I am loud and crude and I won’t let you fuck me the way you like, and I refuse to call you daddy or bigboy or any other gross dirty talk you’re into.”

As a lover of fairytales, I would not want to dwell in Rosso’s pages forever. There is too much gore and too much rage. Yet, for all their indignation, Rosso’s fairytales have their charms. These stories are reworkings of the original tales, perversions in the best sense that use fairytales to hold a mirror to our society. They are tales reflecting the dishonor created in our souls through structures of supposed propriety whose actual goal is the repression and exploitation of half our citizens.

Heavy stuff, maybe, but the wit is there. In the opening tale, Beauty escapes from an arranged marriage with the sneaky, greasy-handed manipulator her family intends for her, straight into the arms of a carnivorous Beast. The most famous reworking of this tale is Angela Carter’s “The Tiger’s Bride,” a much slower-paced but equally ironic tale. In Rosso’s version, the “rescuer” takes our heroine to his castle, intending to fatten her as the centerpiece of a fine meal. Meanwhile, he makes the unfortunate mistake of having her cook for them both, and he is in turn slowly poisoned by her succulent cooking. As he begins to succumb, the Beast hallucinates that she is a “candlestick or a teapot,” a hilariously sinister evocation of Disney’s Busby-Berkeley-like production number in “Be Our Guest.”

Indeed, this is a world worth exploring. In fact, for all its fairytale quality, the world of She is a Beast is our own world, a place of human deception whose malignity can only be subverted by those who understand, and can dominate, the power-hungry. Rosso’s remedy for the ills of womankind is a brutal lex talionis. Her Cinderella uses her virginity as bait, attracting suitable candidates to a round of speed dating at the ball, manipulating the most desirable gentleman into an iron-clad nuptial contract that consolidates his family’s vile secrets to imprison him forever in an unequal relationship. She notes, “you have to be devoid of propriety to become business savvy,” and proceeds to demonstrate her chops.

My favorite is Rapunzel, whose keeper in the tower, the Enchantress, pimps her out to a range of “suitors” who “bartered and herded, whipped and flayed her, as though she was cattle. An expensive hide full of tender meat. They needed [her] to make them feel something.” It is these men that Rapunzel ultimately evokes to help her cut her hair and escape. At her summons, “[f]lashes of suitors appear … in the tower, like ghosts, reenacting the past.” A catalog of former lovers follows, but Rapunzel’s help, her hope for escape, does not ultimately come from these men. Instead, as befits this universe, salvation emerges from an unexpected source.

In each of Rosso’s tales, the limitations of civilization emerge clearly, especially for women, who are hemmed in and brought low by its inequitable expectations, like young Celia, who is executed by her father for promiscuity and becomes the Siren of Wailing Lake. At the same time, for each of these heroines, the attractions of the wilderness promise “a life of twisted paths and bold adventures” that can only be achieved by thinking for yourself, and relying on your own inner resources. In some of the stories, these bold adventures are sadly foreshortened: we do not see them played out as we hover with our heroine on the edge of her adventure. But when Rosso launches a Beauty or a Cinderella, the tale carries us into a sly adventure we would not want to miss.

She is a Beast

by Christina Rosso

APEP Publications

Published on May 1, 2020

60 Pages

Eva Thury teaches in the Department of English and Philosophy at Drexel University in Philadelphia. She once described herself on PBS rather grandiosely as having “a black belt in mythology” as a result of co-writing Introduction to Mythology Contemporary Approaches to Classical and World Myths, 4th ed. (Oxford 2016) with Margaret K. Devinney. She is also the translator from the Hungarian of Sándor Bacskai’s One Step toward Jerusalem: Oral Histories of Orthodox Jews in Stalinist Hungary. Though trained as a classicist, Thury sees herself as a student of popular culture, pursuing interests in everything from vampires to Sandy Skoglund’s radioactive cats.