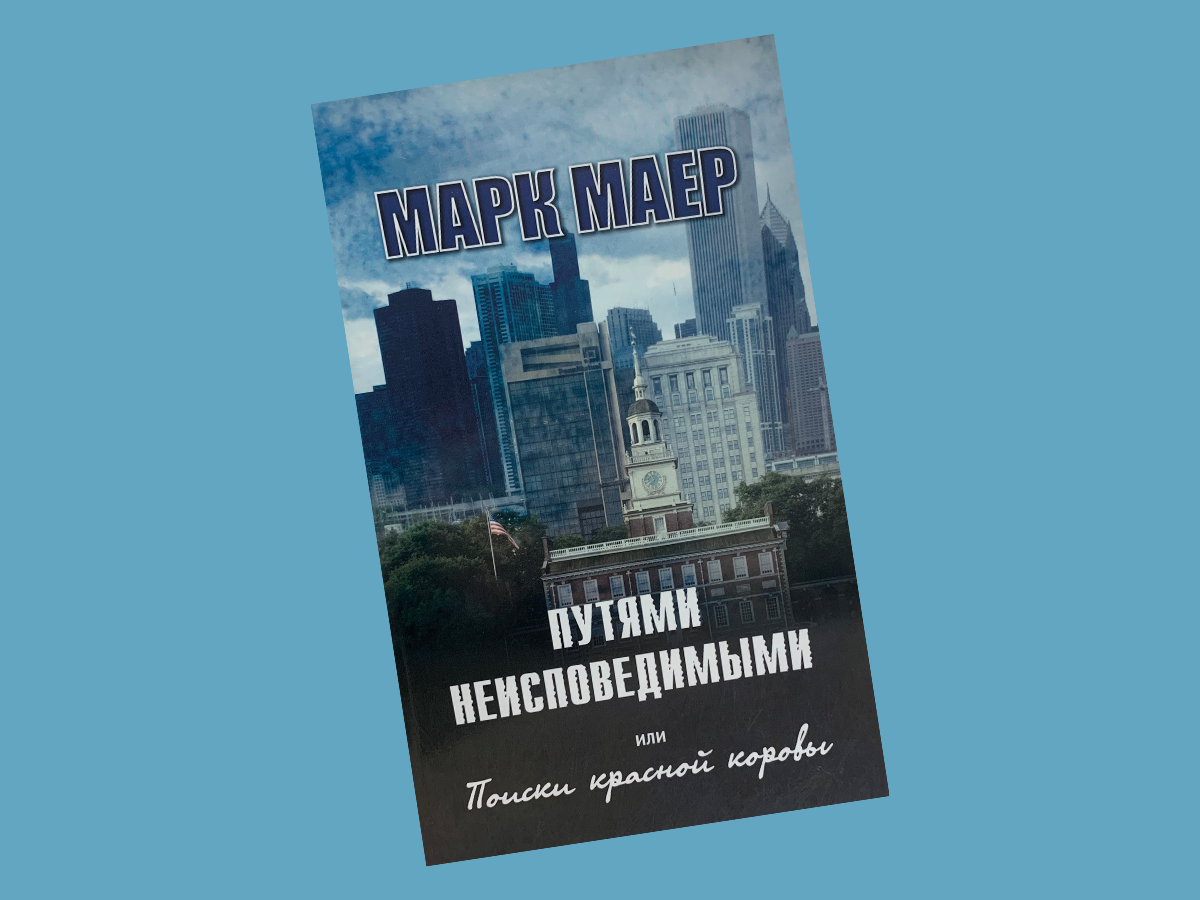

Mark Maer is the author of a Russian romance that came out in 2012, Путями Неисповедимыми или поиски красной коровы, which roughly translates to Mysterious Ways or the Search for the Red Cow. This book follows the journey of a boy born in Ukraine right on the eve of WWII and his subsequent struggles and adventures throughout life as he grows up and eventually settles with his family in Philadelphia more than 50 years later. As he’s also one of my extended family members, I had the pleasure of sitting down with him personally to ask him a few questions about his book, writing, and even his life.

*This interview was originally conducted in Russian and then translated to English by me

Elizabeth Mekler: Growing up, I would always hear the stories about how hard it was back then and that my generation will never understand the full story. Is this why you decided to put the stories to paper and publish them, and if it isn’t, then why did you? What made you decide to put the stories to paper, to make them public instead of keeping them in the family?

Mark Maer: When I first started writing this, it was right around the time that my sister died back in 2008. Her death was the catalyst because I realized that I was the last surviving member from my family and that if I didn’t share the story, it would be lost. My sister never got married and had kids of her own. I have one son and while he’s aware of the struggle that we faced, before and after he was born in 1962, he doesn’t really know the whole story. Originally, I thought about just sharing the story with him through letters but then I talked with your grandmother, my wife’s sister, and realized that though we lived in different places, our stories are pretty similar and so I thought about what would be the best way to share the story with the entire family. At that point, I realized that the best way to do that would be to actually write this book; that’s where the idea came from. It was never a way to profit, it was just a way to share the story across multiple generations and countries. If someone unrelated to us happens to read it, then even better because the stories are fading and no one’s really writing down the unedited truth, at least in my experience.

EM: This novel is classified as a romance in Russian. Would you classify it as such? Do you think that the true genre and meaning of the book gets lost in translation?

MM: No, I would never classify my book as a romance. One of the hardest things about translating stuff is to make sure that the meaning is still there. As you noted when you were trying to translate the title, some things just don’t translate. My book was never intended to be what Americans classify as a romance but rather what Russians classify as a romance, meaning a novel. That’s the real genre of the book, just a novel, specifically, the novelization of my life. However, even if some of the words and phrases get lost in translation, the reader should still be able to take away the meaning of the book, which is that life goes on.

EM: In the book, your main character goes from living in Ukraine, then Russia, followed by Mongolia, and Israel, before finally settling here in Philadelphia. Are there any parallels between the boy in the book and your life? Is there any truth behind the events that take place in this novel?

MM: There are a lot of parallels between my life and what the character goes through in the book, including the locations and places mentioned. I was born in Ukraine in 1934 to a family with four children, including me, and both of my brothers died during the war, either because they were forced to fight in the Red Army or because they weren’t lucky enough to escape with the rest of us. We managed to escape to Russia, which is actually where I met your grandma’s sister.

EM: Having lived in so many places, which would you say is the best and why?

MM: I loved living in Mongolia because it was close enough to the USSR that it was easy enough for me to visit my friends but it was also far enough that there was less censorship and more access to the West in a way. My wife will probably tell you that Mongolia was more fashionable than Leningrad (St. Petersburg), but then this interview will last even longer.

EM: Do you think that if you stayed in Israel you would’ve written this book?

MM: I honestly don’t know because I started this book because my sister died. Maybe if I lived close enough to her and managed to get to her in time, I wouldn’t have, but I don’t know.

EM: What was the hardest part of the writing process for you?

MM: I knew right off the bat that there would be a lot of personal things within the book, but the hardest part was deciding what needed to be said and what should be kept a secret. It was only hard for me to dissociate and write from a relatively objective point of view. I never realized how hard that would be until I had to write the chapter that deals with the majority of my family being separated and most of my siblings being shipped off to various camps. Every other personal event that had a lot of emotion attached to it was just as hard.

EM: How long did it take for you to go from your first rough draft to the final copy? Is there anything that you wished you included, or excluded, in the published version?

MM: It took me roughly five years to go from the first rough draft to the published manuscript. It took me roughly two years just to finish the rough draft and get enough courage to actually send it off to a few publishers. Without giving away too many spoilers, all I want to say is that America was nicer and gave me more hope 10 years ago than it does now and maybe I should’ve held off publishing it till now.

EM: What did a typical writing day look like for you? Were there any changes from your typical day?

MM: So usually, I would wake up in the morning around eight, watch or read the news while I have breakfast and then go about my day. When I was writing, not one day would stay the same. I actually had to stop sleeping in the same room as my wife because I would be up writing all hours of the night. I actually discovered that I’m naturally a night owl then; imagine finding that out when you already lived through most of your life. Basically, my writing days differed from day to day. Sometimes I would just write until I couldn’t, and sometimes I had to force myself to finish writing a specific section (the really emotional parts happened like that more often than not).

EM: Part of the reason that I decided to read your book was to get a clearer picture of what it was like to grow up and live during that time. While writing this, did you find yourself feeling nostalgic about anything, missing anything?

MM: One of the things that you have to understand is that while my experience is similar to thousands of other peoples’, not everyone had the same one. If you were well connected, you were much better off and were lucky enough to get warnings ahead of time. If you weren’t, then you knew that and tried your best to just blend in. That’s something that I don’t miss, the constant paranoia. There are multiple things that I do miss, but a lot of them have to do with my age and taste. The music was much better in the ’60s-’90s, both official and underground.

EM: Did you learn anything while writing your book? Are there any specific feelings that you want to evoke in your readers? Any specific messages that you want to get across to your readers?

MM: The main message that I want to spread to my readers, those outside the family anyway, is that life goes on. However, I also want them to feel what it was like to live through those horrific events. I want them to think about what they would feel like if one day out of the blue, they get separated from their family and then have to start all over without anything but the clothes on their back. I also want them to understand just how quickly people can turn on each other. I lived during the times when I knew that I couldn’t trust anyone because they could all be government spies; nowadays we live in a world where we don’t have to worry about people but rather our technology and that was one of the most frightening things that I learned. Let’s just say that I’m never using voice-to-text again.

EM: I’d like to thank Mark for sitting down and talking with me and rehashing some of his most painful, and valuable, memories. Путями Неисповедимыми или поиски красной коровы (Mysterious Ways or the Search for the Red Cow) is an emotional, thought-provoking, and inspiring tale about living through some of the hardest times and conditions and continuing on. It can be found in a small Russian bookstore, Книжник, in far Northeast Philadelphia now.

Elizabeth Mekler is a senior at Drexel studying bio with a concentration in organismal physiology. She dreams of getting into med school and becoming a trauma surgeon. If she’s not studying for the MCAT, or volunteering at her local hospital, then she can be found either reading some historical fiction or science fiction, tinkering with electronics, watching Doctor Who, or playing/listening to music.