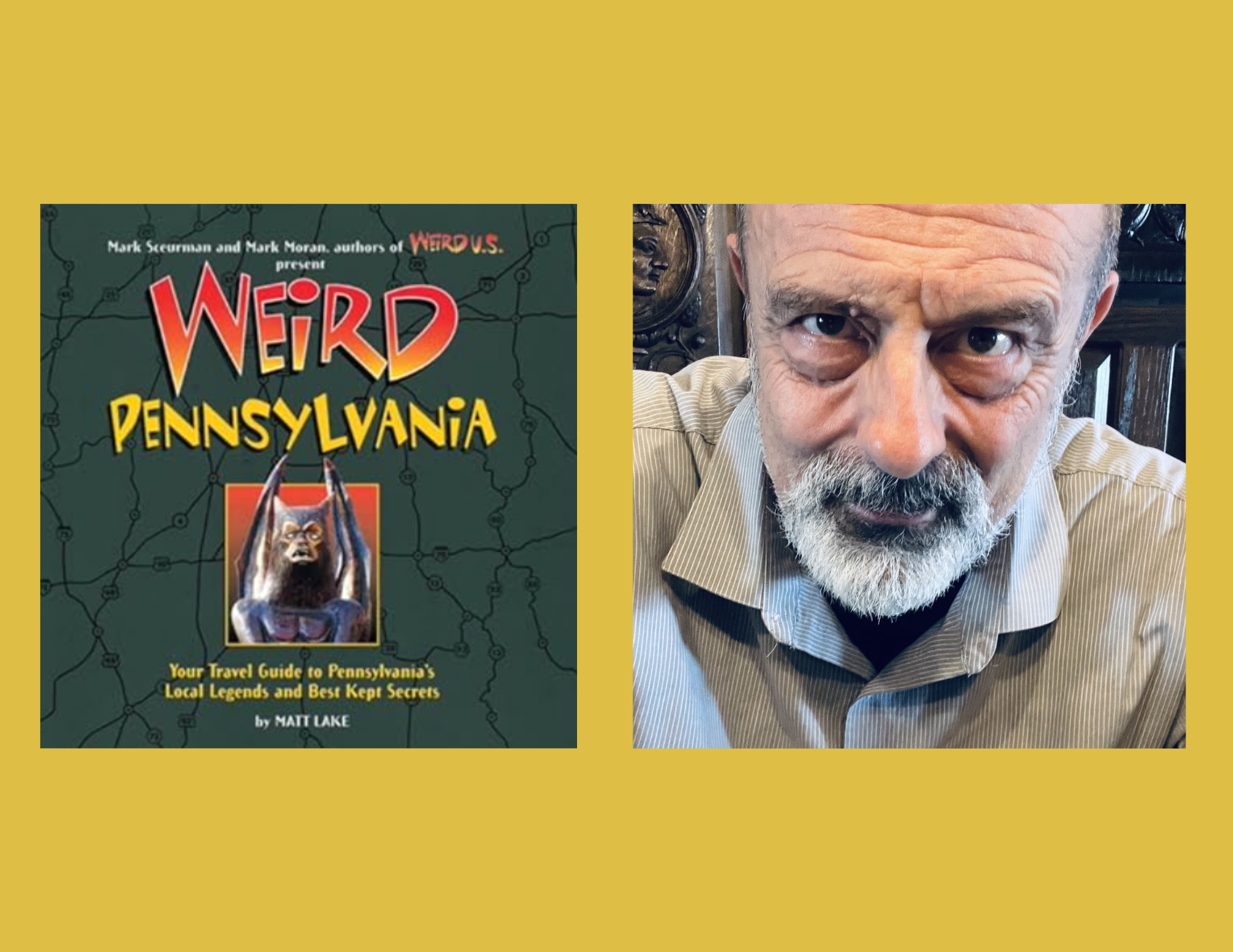

Matt Lake is an Eastern Shore region folklorist and writer who’s been active for several decades. He’s most well-known for Weird Pennsylvania, Weird Maryland, and his role in the cult class horror film Butterfly Kisses, among dozens of other publications. He agreed to sit down with me to discuss these works and more in celebration of Weird Pennsylvania’s 20th Anniversary.

Audrey Boytim: How did you get involved in writing for the Weird… series? What was it like to write for a series with a pre-existing structure?

Matt Lake: I’d been freelancing for five years and taking on all kinds of assignments. My assignments were a stew of 500-word magazine reviews, 750-word news articles, how-to instructional articles, longer feature stories, and highly illustrated how-it-works features on subjects like the Global Positioning System or how sports networks overlay the virtual yellow first-and-ten line on the field during football games. It was all work-for-hire for newspapers, magazines, and web sites, with the occasional book edit thrown into the mix.

I’d worked on a few technology books at that point and took on an assignment to finish a paperback for Sterling Publishing that someone had abandoned mid-project. The publisher must have liked what I did, because the next gig they gave me was editing the book version of Weird N.J.–ten years’ worth of weird magazine articles in one book. It was a joint venture between the Marks (Mark Sceurman and Mark Moran) who publish the magazine Weird N.J. and Sterling Publishing out of New York. That book really took off, so they brought me on to edit Weird U.S.–the same type of material but about the whole country. Then they opened the series up, with a goal of making a book for every state. So, I jumped at Weird Pennsylvania and lined up Weird Maryland for the following year.

AB: What is the research and writing process like for these books? Were you physically going around, finding place after place, or was it a primarily archival process? How did you decide what to include and what to cut?

ML: Mark and Mark provided letters and stories from Pennsylvania that they’d collected over the years from contributors and readers. After two years line-editing the series, I knew the kind of story that belonged in the book, and I’d already begun to flesh out the chapters for Pennsylvania. A lot of the prep for the book started with me obsessively reading books about Pennsylvania in libraries, flipping through books in bookstores, and visiting various counties’ historical societies to look through their archives. I also attended conventions like the East Coast Bigfoot Society annual meeting. This was twenty years ago and the Web search options and paranormal and cryptid social media groups were much sparser than they are now.

I collected stories by yammering with people in bookstores and libraries–complete strangers, some of them–and even a clerk in a convenience store. There was also a lot of email and some cold calling on the telephone. I traveled a lot because I wanted to get the vibe of the places I wrote about and also take photographs of as much as possible to support the articles. It was a joy to go places and then write about them because I’d spent more than a decade basically deskbound and writing. The change of scenery was great–and I enjoyed the subject matter too.

I had my own voice to work with, but the structure and the tone were all on the Marks. I can’t remember if I submitted chapter outlines for approval before I wrote them, but I’d designed a spreadsheet and had the thing structured so tight that the process of writing it was basically filling in the blanks. It wasn’t as if the writing itself wasn’t creative–it’s that making the structure was part of the process, and it freed me up to enjoy the actual writing. So much so, I wrote way too much. I overestimated how many stories the book needed; I submitted about fifty pages too many. And thank goodness there were editors in the mix; they sliced and diced–just as I had done for the two previous Weird books–and I left that to them.

The editors also added maybe a half-dozen stories that I didn’t know about until the page proofs arrived, and that was fine–more than fine, it was great. The collection wasn’t exactly what I’d put together, and I’d probably have edited out different stories to bring the thing down to the right page count–but the great thing about working with an editorial team you trust is that the whole becomes greater than the sum of its parts. It’s better when you can enjoy the finished product along with others who are equally invested in it.

AB: What, if anything, would you change about Weird Pennsylvania now that twenty years have passed? Is there anything new that you would include?

ML: I’m very proud of the book’s contents and layout and production values–it holds a special place in my heart. But like anything you put out on a deadline, there’s always something you look back on and feel you could do better. I cranked out a chapter a month to get the book done, and I still think the balance of the stories was solid. But the Western of the end of the state deserved some more love. There was a great Pittsburgh story in the first draft that we’d laid out in the galleys but cut for space. I’d have loved to include that in the original book. And I found out so many more things as I traveled around in the following years. There’s a front lawn full of car bodies with giant metal insect legs in a home in Erie County. There’s a terrific home museum up a hill in Pittsburgh called Trundle Manor. It’s run by a couple who are equal parts Addams Family and the greaser clan from John Waters’ movie Cry Baby. You can book a tour of the ground floor of their home–you just show up at the appointed time, walk past the hyperbaric chamber on the front porch, knock on the door, and Velda Von Minx will show you their bizarre collection. In the minus column, there was a cool retro attraction called Roadside America that was in the book, but closed down after the pandemic, so I’d have to cut that out. On the plus side, another called the American Treasure Tour opened up, and I’d definitely include that.

AB: What are your favorite weird things in Pennsylvania listed in the book? The Philly area? Pennsylvania is a huge and varied state; on reflection, where do you think the weirdest region of it is?

ML: Wow, that’s such a tough one to answer. I love bizarre roadside nonsense, but I also like weird collections and museums. I’m a big fan of cryptids and cemeteries, and abandoned buildings instill a sense of awe in me. All of these are so well represented across the Commonwealth that I’m spoiled for choice. But I have a tremendous love of the work of the artist Isaiah Zagar who put up murals guerilla-style all over the streets of South Philly, including a massive three-story, three-building mural that’s now called the Magic Garden. It began life as a vacant lot surrounded on three sides by tall buildings. Zagar covered the walls with highly stylized murals and constructed walls made of bottles, bicycle tires, and all kinds of recycled junk. He tiled the floors, put in secret messages, and transformed an area of urban blight into something beautiful. And the guy was a real sweetheart to my kids when they were young–which is always a way to win the heart of a dad.

A fellow out in Pittsburgh did something similar, buying vacant buildings for a pittance and making the walls and grounds into a colorful folk-art treat–that’s a place called Randyland, and it’s another story we missed in the book. So the state’s sandwiched by weird outsider art. As for strange collections, I love the Mütter Museum (of course!) and a big concrete castle out in Doylestown full of pre-Industrial Revolution tools of various trades–that’s called the Mercer Museum. It’s an architectural oddity full of weird old stuff, and it also houses a historical society archive–everything a growing boy needs! Traveling north is a large standing stone park called Columcille that’s almost a religious site. I make pilgrimages to all of these places often.

AB: From both your career and our own acquaintanceship, it is clear that local and regional folklore is a major presence in your life. What are some fun ways this passion manifests? What are some ways for would-be folklorists, urban explorers, and weavers of urban myth to get started?

ML: Growing up in the 1970s, I was surrounded by books filled with monsters, ghosts, UFOs, dark history, and anomalies. I put these things behind me when I was carving out a career for myself, but I felt a healthy wave of nostalgia for them. When the Weird book series fell into my lap, I had full license to pursue my career AND that weird nonsense I’d put on the shelf for a couple of decades. It was great! But it challenged me a lot. I was the kind of writer who had learned to verify my sources, synthesize a 500-word story out of several different sources, and to make sure everything was factual and accurate. This made ghost stories difficult to write, because it’s a folk-art form–the antithesis of journalistic nonfiction. But site-specific ghost stories when they are written down are often embellished in ways that veer into fiction–and not very good fiction at that. You have to get forensic in reading different accounts of the same story, and figuring out what was invented by Edwardian country priests to convey a message, and what was authentically passed around between 18th century farmers to while away the long winter nights. Like anyone who spends any time with the editorial production process, I was reluctant to submit anything that fact-checkers could flag and make me verify. I had to switch gears when approaching folklore.

The one story that broke me as a journalist was the Maryland legend of the Black Aggie–a statue that comes to life in a Baltimore graveyard. I fished out a box of oral histories from an archive in the University of Maryland and thought I’d hit the motherlode–until I read two dozen completely different and incompatible accounts that were impossible to reconcile into a single narrative. There were maybe six different ways she would kill people who visited her grave site, a dozen different physical descriptions–she had glowing red eyes and glowing green eyes, and no eyes, and a whole lot of other contradictions. The very details that made a science and technology journalist throw up his hands in despair are what made it great folklore.

AB: Let’s shift gears to the obligatory Butterfly Kisses questions… but first, I’ll provide some context for readers.

In the late 2010s you worked with filmmaker Erik Kristopher Myers (z”l) on the now cult-classic horror film Butterfly Kisses, which is a movie entirely about regional “fakelore” in the Baltimore suburbs (more specifically, in my own hometown of Ellicott City). In the months leading up to the release, several posts about the film’s central figure were made online, graffiti of said figure was sprayed in several popular urban exploration sites, and a guerilla marketing campaign for the urban legend itself (not the film!) sprang into place.

What was it like to work on a project devoted to a new and artificially propagated urban legend? Have you seen this sort of thing happen before?

ML: When Erik first contacted me via email and we spoke on the phone, I hated the idea of being involved in his project but thought it would be a great thing to watch when it came out. It reeked of fakelore–stuff that was made up by professional writers to look like folklore but either make a buck or push a particular agenda (like Victorian priests making up sentimental stories of pious little children doing things to soften the hard hearts of the unbelievers). Horror figures like the wet ghost in Ringu and its American remake The Ring are one thing–I can dig them as fiction, but the idea of endorsing something like that as a real story set alarm bells ringing in my head. He suggested we meet and chat about it, and by the end of our conversation, I was a convert. He wasn’t trying to get me on board to give his Peeping Tom creation credibility–he wanted me to rip into it, dispute and disbelieve–all the things I want to do when I hear made-up stories passed off as truth. This appealed to the folklorist and the journalist in me. And it gave me the chance to watch a microbudget film being made, which was an opportunity I’d never had before.

AB: For several years afterwards, Butterfly Kisses influenced your career as a writer in one way or another. You wrote for a short story collection focused on the “fakelore” at the heart of this movie. You took part in writing and speaking collaborations with other people you’d met through the movie, including K Patrick Glover, whom you co-wrote a children’s book with. What was it like for these connections to grow?

ML: It was a weird time for me in general. I was moving house, shifting away from freelance writing as a major source of income, and making friends outside my regular group. I really bonded with several people from the movie, and remain in touch with them to this day. It was an eye-opening experience to see a dedicated filmmaker and serious actors doing their thing–it was a profession I’d never looked at closely, and it reminded me of many ways of the best types of publishing projects–lots of different talents and strengths coming together to create a whole. And it took several years to complete, which meant we had to stay quiet about it and shiver with anticipation.

I started to work on an epic poem in the style of Keats or George Crabbe that skirted around the Peeping Tom folklore–it was a way of dealing with that huge gap between working on a film and waiting for it to come out. In the meantime, Erik and Seth were seeding all these Web sites with backstory about the legend and the character Gavin York’s descent into madness. And then K. Patrick Glover came onto the scene with a proposal to do a collection of short fiction on the subject of Peeping Tom. I loved that but I’m not a fiction writer, so I thought I had nothing to bring to the game. Except that I’d written a long poem as a writing exercise and with a little framing, it fit right into the book.

The real kicker was when a regional history writer named Shelley Wygant wrote a book on Ellicott City folklore and included Peeping Tom in it. I was genuinely horrified that the thing appeared in print as if it were a real story. Shelley thought it was funny and came on board to write for the collection In The Blink of an Eye–but I had some real reservations about this great microbudget publicity stunt being seen as a real story. I learned later that Ellicott City’s historic society was training dark history docents to include the story as if it were true–and I’m now on a mission to set the story straight, while also saying it’s a hell of a movie and well worth a watch.

I also put out a book with Seth Adam Kallick, who played Gavin York in the movie, and am tinkering around with some other projects to do with him. He’s a creative dynamo and a lot of fun to work with.

AB: Does this project prove that Maryland is weirder than Pennsylvania, or just differently weird? Philadelphia did spawn Eraserhead…

ML: Don’t ask me to pick my favorite baby! I love both states, and identify with them both. Which may be a little weird for an obviously English guy to say, but I can’t help where I’m from: I can help where I have chosen to live in recent years, where my friends are, and where I feel compelled to visit regularly to feel fully myself. And that’s these two weird states. If we’re talking which state spawned the weirdest stories, you’ve got David Lynch in Philly, but John Waters in Baltimore. And you’ve got the Blair Witch Project in Burkittsville vs Night of the Living Dead in Pittsburgh. Or in the folklore of cryptids, the Goatman in the DC beltway versus the Squonk in western PA. All in all, I think that Maryland embraces its weirdness a little tighter than Pennsylvania does–by which I mean that Marylanders seem a little prouder to wear the title of Weird than Pennsylvanians. But they’re pretty much neck-and-neck on the weirdness front.

AB: What’s next for you professionally?

ML: With the 20th anniversary of Weird Pennsylvania this year and Weird Maryland next year, I’m hankering to write sequels or companions to both books. That’s not underway yet, but I really want it to happen. What’s actually on the cards is a ghost book that I’m currently writing for the Strasburg Rail Road in Lancaster County, PA. I did some narrations for a haunted train ride there last year, and they want to continue developing that this year. So I’m elbow deep in ghost lore right now–and only talking to you because I should actually be writing that. You know how writers avoid writing by doing everything else, right? That’s what’s happening here.

On another front, along with two friends (Brian Goodman and Susan Fair), I have assembled a Maryland book of cryptids and monsters that I’m extraordinarily pleased about. The three of us were setting the pace for each other, slapping down some great stories to a chorus of “Damn! That’s good–I need to up my game here.” We weren’t trying to outdo each other so much as not to let the others down, so we could put out something we could all be proud of. And we are. Monsters of Maryland and Delaware came out in a limited edition print run, and we’re looking to get it into distribution soon.

After that…well…I’ve got notebooks and spreadsheets full of outlines. All I need is to prioritize the projects, get them written, and get them published. Sounds simple…we’ll see how simple it turns out to be!

Audrey Boytim is an English major at Drexel University currently developing her senior project in horror metafiction. She is a multimedia artist with several songs, short films, and stories published, and she is currently writing a full length independent horror film entitled “The Bureau.” In her free time you can find her volunteering at Wooden Shoe Books, biking around the city, or kvelling in her yiddishkeit.