Tom Huddleston’s coffee-table book David Lynch: His Life, His World seeks to memorialize the famous once-Philadelphian filmmaker by interrogating the connections between Lynch’s environment and his career. This interrogation, which might fall into tacky analysis in the hands of a less graceful writer, occurs through a subtle, largely chronological narrative which weaves its way through the book. Huddleston’s connections go from the immediate to the long term, and from the nuanced to the obvious. (In one such example he ties Lynch’s burgeoning practice of Transcendental Meditation, a stress-reducing meditation technique which Lynch spent much of his life as an advocate of, with his choice to add an optimistic ending to his film Eraserhead.) The influence of Philadelphia on Lynch’s work is an example of a long-term connection which Huddleston examines.

Huddleston’s direct focus on Lynch’s time in Philadelphia is brief. The story of Lynch’s time living in the Callowhill neighborhood and attending the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts is oft-repeated in books about Lynch. Despite this familiarity, Huddleston emphasizes the importance of the city to the director’s vision and leans on Lynch’s own quotes in doing so. “Philadelphia is my greatest influence,” Huddleston quotes Lynch as saying. Next to photos of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and the skyline of the Callowhill neighborhood, circa 1968, Huddleston describes specific influences which the city held for Lynch’s work, from “burned-out storefronts and abandoned homes to factories and industrial spaces.” Huddleston devotes the same time and space to describing Lynch’s shifting artistic vision and his growing interest in insects, decay and rot. Seeing the images, reading about the city itself, and then reading about Lynch’s work creates a trifecta effect that infuses the city into the reader’s understanding of Lynch’s films.

This understanding only grows as Huddleston moves through an exploration of Lynch’s work more broadly. As almost every biographer does, he takes care to emphasize the immediate connection between the urban decay of 1960s Philly and the nightmarish, “can’t get there from here” city of the director’s debut, Eraserhead. Through his invoking of Lynch’s own linking between Philadelphia and the darkness of the work and Huddleston’s own connection of Transcendental Meditation and the film’s ethereally optimistic conclusion, Huddleston sets an interesting polarity within Lynch’s work. This polarity sees Philadelphia as the inspiration for all that is dark and nightmarish in the director’s catalogue and Transcendental Meditation as the inspiration for all that is spiritual.

The city is referenced several other times in the book. The most interesting thing which Huddleston brings to the table is his repeated reference to motifs which he first identifies in conjunction with Lynch’s time in Philadelphia. The abandoned buildings and urban emptiness first identified as early urban influences are recalled in Huddleston’s telling of Lynch’s urban exploration and photography during the shooting of The Elephant Man in England. The urban abnormality beneath a peaceful suburban life, a theme explored in Blue Velvet, is subtly linked to Lynch’s own urban adventure after his suburban childhood through Huddleston’s retelling.

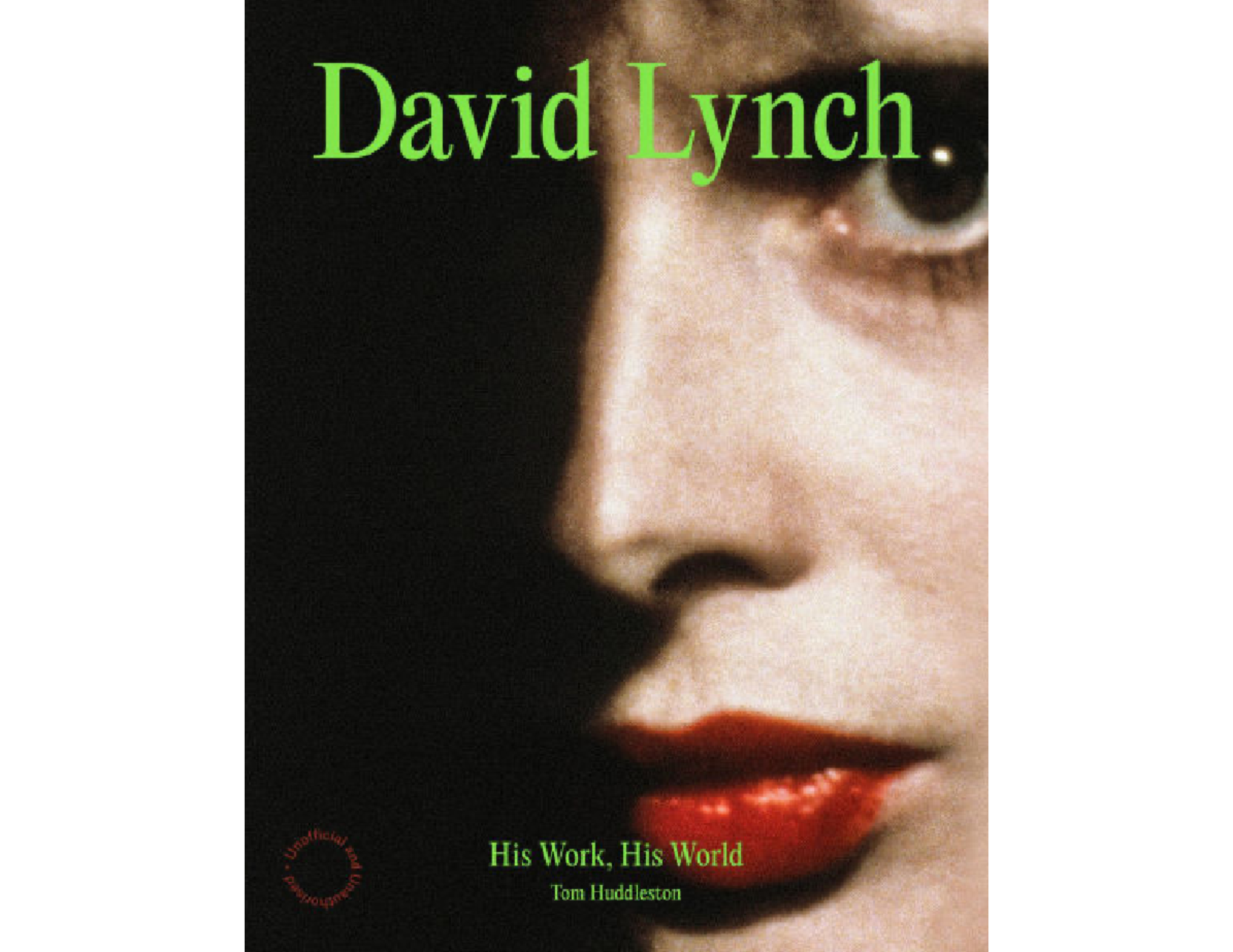

These themes have all been explored before, by writers such as Chris Rodley in his Lynch on Lynch or even David Lynch himself in his own Room to Dream. Tom Huddleston brings two unique additions to the table in his retelling of this mythologized story, both in terms of Lynch’s time at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and his career in general. The first is that the coffee table book format allows Huddleston to make use of a large number of visual references to Lynch’s work and influence. This adds a viscerality, which is thematically appropriate when discussing a visual artist, to what he describes. Images include stills from Lynch films and scans of Lynch paintings, behind the scenes photos, abandoned buildings, the Maharishi, and more. In this sense, Huddleston seeks to create a mélange of influence.

Huddleston also seeks to retell an oft-told story with a balance of brevity and connection. His narrative is quick and moves from epoch to epoch without much dallying, yet he still takes the time to focus on the specific influences of Lynch’s work in each of those eras. Huddleston further returns to reference those same influences, repeatedly, throughout his narrative. In doing so, he seeks not to retell an often-biographed life story. He rather seeks to use the broad strokes of that story as a container to tell a different story about the times and places where Lynch lived and how those times and places have connected.

Huddleston doesn’t entirely bring Lynch home. He places the filmmaker in the context of many spaces at many times and never seeks to erase any of their influence. Nevertheless, by returning our focus to Philadelphia as a foundational space in Lynch’s life and career, Huddleston recontextualizes the director’s entire momentum into a response to the space where it was first born. This reframing may not do much for Lynch fans, who already know the story and already have their own associations with the parts of this story that resonate most with them. This reframing will, however, do a lot for a city that will always benefit from remembering the art and wonder that it is capable of inspiring.

You can order Tom Huddleston’s David Lynch: His Work, His World here.

David Lynch: His Work, His World

Tom Huddleston

Frances Lincoln

September 11, 2025

240 pages

Audrey Boytim is an English major at Drexel University currently developing her senior project in horror metafiction. She is a multimedia artist with several songs, short films, and stories published, and she is currently writing a full length independent horror film entitled “The Bureau.” In her free time you can find her volunteering at Wooden Shoe Books, biking around the city, or kvelling in her yiddishkeit.