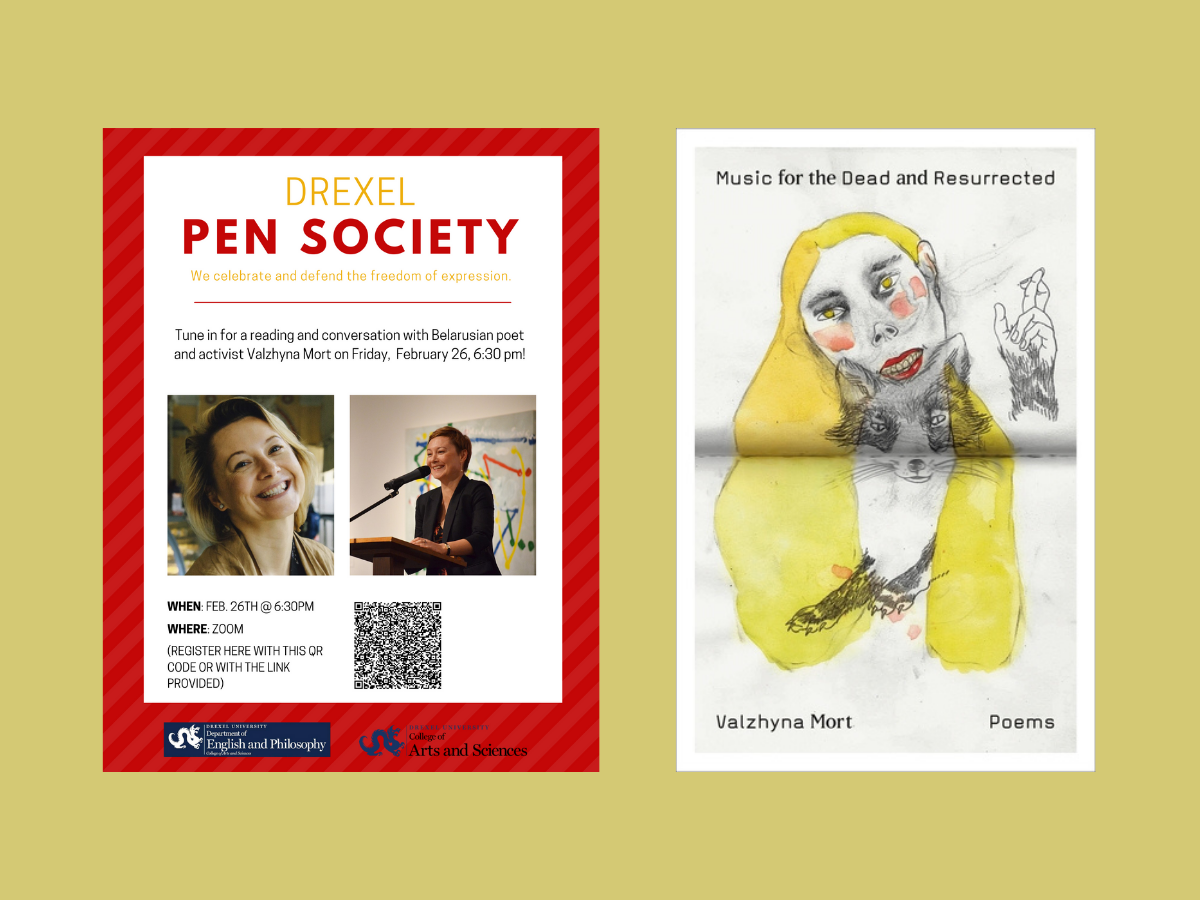

On Friday, February 26th, Valzhyna Mort, award-winning Belarusian poet and translator, answered questions about writing and activism and shared poetry from her newest collection, Music for the Dead and Resurrected, with the student organization, Drexel PEN Society, and other members of the Drexel Community. The event was hosted by Professor Harriet Millan, and the discussion was guided by members of the Drexel PEN Society.

Mort drew attention to the recent arrests of old women charged for reading books in Belarusian on the train. She said, “the question of language is very political and traumatic in Belarus.” For a little context, the nation of Belarus is in political turmoil at the moment. President Alexander Lukashenko was re-elected on August 9th 2020, however many citizens believed that the election was rigged to keep him in power. Protests broke out to call for him to step down and allow Svetlana Tikhanovskaya (the opposing political candidate and wife to Sergei Tikhanovsky, who was imprisoned to prevent his bid for election) to take over. The fixed election and the protests in response have led to a crackdown on any behaviors deemed “treasonous” by the government and police; 258 citizens of Belarus are considered political prisoners at the moment.

Echoing the present, the history of Belarus shows a nation wracked by war and pain trying to find its identity amidst imperialist influences from the West and East. Mort focuses on family and language as a link to identity throughout her poetry because she says, “like a lot of people from Eastern Europe, I come from what I could call an empty family archive, which is to say that we do not know our lineage because the 20th century was an unbelievably traumatic century.”

The use of her languages is an essential part of her writing. She says, “we write in order to arrive to some kind of understanding that is impossible without submitting to language, without allowing language to lead us away from who we think we are from what we think we are.” Mort uses both English and Belarusian in her poetry, and she knows Russian. Language is also important to her because of the lives and relatives she lost in her family history. She says, “I look for language to talk to my dead… to try to reach them, because without them, I feel incomplete.”

Mort’s relationship with language factors into her literary influences as well. She admires late 20th century Polish poetry because not only did “Polish poets…f[ind] the language to talk about violence, the experience of cruelty, the experience of seeing how human beings turn into something that we would call inhuman and act inhumanly towards each other,” they found a way to celebrate the joys of everyday life as well. Mort sees this ability to turn tragedy into joy and laughter in Belarusian people as well. The resilience of Belarusians despite the tragedies that have occurred in their past shows in Mort’s work. Even though Belarus has been under the influence of greater political powers, they still find a way to keep going, to uncover their history and forge a national identity.

Although Mort is a writer who uplifts Belarusian causes through her writing, translation work, and organizing of literary events, she doesn’t believe that she is an activist. However, she does believe “that the life of a writer, the writer, or the life of an artist is the life of solidarity and the life of mentorship and help, you have to help everywhere you can.” She sees her life as deeply intertwined with politics and history.

The moment that left me speechless during the conversation was when Mort mentioned a conversation she watched between writers Herta Müller and Svetlana Alexievich, about how language can lead people to realize the greater truth of what’s inside themselves. She said, “Right, we think that, yes, we are so shaped by our histories, by our private experiences, but also at the same time we’re having the experience of being this tiny, tiny little creature in the huge cosmos and once we get in touch with that, like that’s what I always want to reach because it’s not always easy to reach that. We have those moments, and we call them poetic.”

Mort sees these moments as times when people begin to “think, ‘Goodness…what does it mean to be a human here? What does it mean to leave? What does it mean to leave? Yeah, I think that that’s kind of a moment that a poet is obsessed with…These moments are rare… and also, as you age, I think they happen less and less because our lives [become] full routines… The poet just goes there always consciously. We’re addicted to this moment, we want to return there all the time and that’s what I do when I arrived, so I run. Yeah, I want to run from my personal experience to the stars.”

Mort spent some time discussing how Belarusian embroidery related to her poetry. She showed pictures of some traditional Belarusian embroidery. She said, “There’s a lot of repetition, that’s the main device that I rely upon as a poet. And repetition, of course…it’s obsession, right? Obsessed people repeat the same things, and repetition is also very claustrophobic… Repetition also is of course a way to think that nothing is truly repeated.” She relayed the history of Belarusian embroidery as a way for people to speak to the heavens. The embroidery could almost be seen as a prayer, and also a road for the dead. People are able to bring comfort and stability to their lives through the use of embroidery. The repetition of the embroidery was recognizable in the poem she read, “Bus Stops: Ars Poetica,” from her latest collection.

The end of the talk was spent getting to know what Mort does outside of her poetry. She spoke about sending cakes and flowers to Belarusians returning from prison, writing essays on Belarus, connecting English and Belarusian poets for translation work and her new skill, organizing literary events. Mort also gave resources on ways students can support Belarusian political prisoners.

Overall, Mort’s conversation with the PEN Society member showed how deeply language and poetry intersect with personal and political history. As poets, we should look to our words to guide us to some hidden truth that inspires us to keep writing and keep going.

Kat Odoms is a pre-junior studying English at Drexel University. She enjoys writing poetry and short fiction. She is currently the Managing Editor of Torch the Veil, a literary magazine, and a Contributor and Co-Editor of IntersEQtions, an antiracist literary magazine from LitEQ.