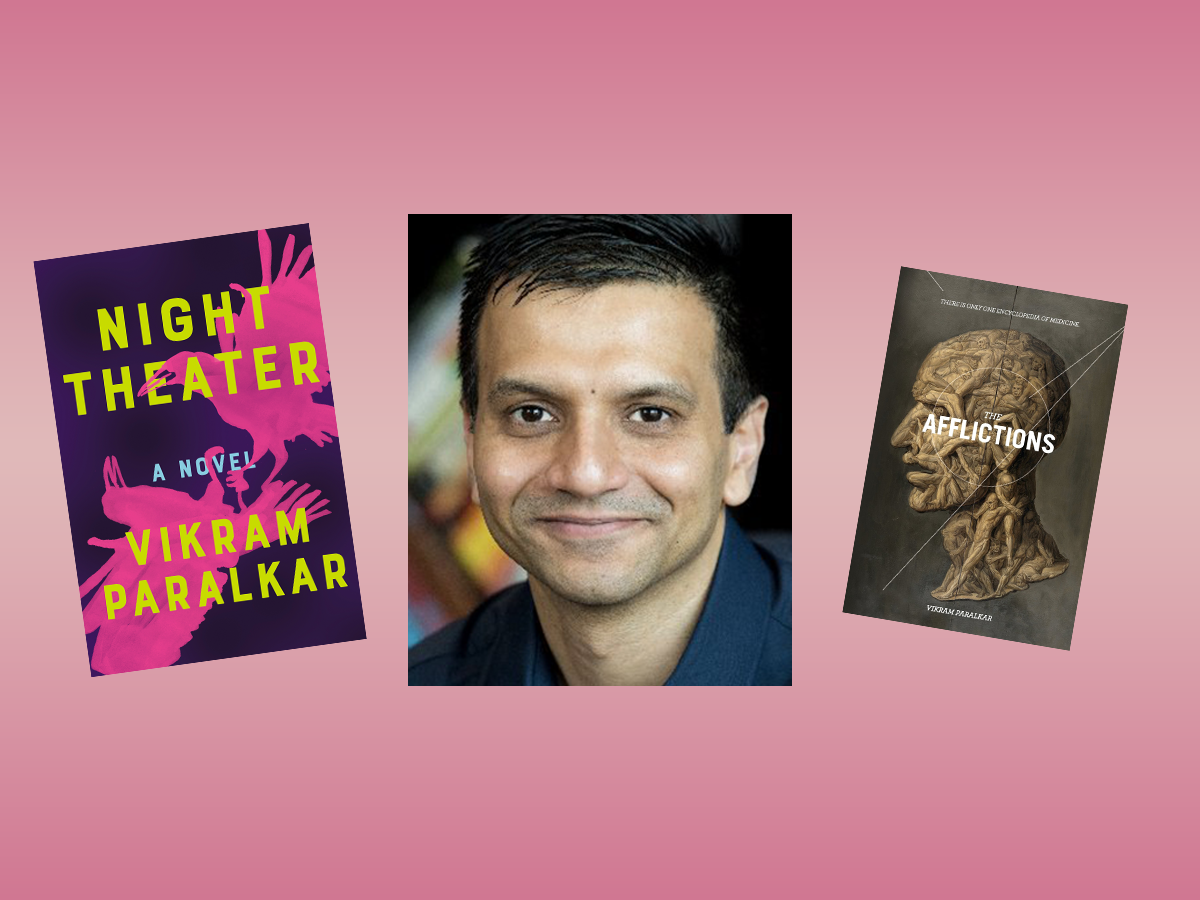

Vikram Paralkar’s new novel is Night Theater. He spoke with Scott Stein on January 24, 2020. (This interview might contain very mild spoilers, but you should read it anyway.)

Scott Stein: Thank you for talking with me. As some readers might know, you are a physician and leukemia researcher at the University of Pennsylvania. You even run your own lab. How do you find time to write novels? Do you have a set schedule for writing? Do you have any advice for writers whose writerly ambitions might be competing with their careers?

Vikram Paralkar: I don’t think I have any particular advice to give—I constantly despair at the zillions of tasks I never manage to get around to doing. Yes, there are a finite number of hours in a day, and finite number of days in a year, and my career doesn’t allow me to go to a writers’ retreat and lock myself in a cabin in the woods for six weeks to hammer out a manuscript (I wish it did!) So, I try to squeeze writing in on evenings and weekends. I’m currently working on a research grant that I have to submit to the National Institutes of Health, and my mind is saturated with writing science (non-fiction!) But once the grant is submitted, perhaps I’ll have a breather, and will be able to devote a few hours a week to fiction again.

SS: Your first book of fiction, The Afflictions (Lanternfish Press, 2015), which I strongly recommend to readers, is an encyclopedia of invented spiritual/magical maladies. Its structure might remind some of Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. What do you make of the connection? When you write, are you conscious of influences on or echoes in your work? Are there other writers you can name that helped shape that book?

VP: Your diagnosis is spot on. Calvino was hugely influential to me, both in my writing as well as in shaping my early thoughts about literature. I didn’t start out with the goal of modeling The Afflictions along the lines of Invisible Cities, but something about the structure of the latter naturally crept into the collection of interlinked and interrelated magical diseases that I was putting together. I think I’m fairly conscious of the influences on my writing (or, at least, I begin to see them with increasing clarity as the work takes shape), and the three other clear influences for The Afflictions were Jorge Luis Borges, Edgar Allan Poe, and Robert Burton. The latter is perhaps the least known to the broader public—he’s the author of The Anatomy of Melancholy, a massive tome about the causes of melancholy that is simultaneously unreadable and yet impossible-to-stop-reading.

SS: Unlike The Afflictions, your new novel Night Theater (Catapult, 2020) tells a story and contains more of the elements of narrative fiction, like extensive dialogue, character development, action, and rich description of setting. Was Night Theater easier or more difficult to write because of this? How did the demands of plot challenge you as a writer?

VP: The two books had very different demands. Night Theater certainly required more focus. My process of writing The Afflictions was episodic (I was also terrifically busy in my medical training), and its structure—a collection of vignettes—allowed that. Night Theater, on the other hand, not only has a plot, but the plot is one that enfolds over the span of one night, leaving very little room for tangents and digressions. I enjoy plots that build like tight logical theorems from foundational axioms that are laid out early in the tale—it pleases the scientific/geometric part of my brain. I found the plot demands of Night Theater invigorating!

SS: The premise of Night Theater is that a surgeon in a clinic in rural India is visited by a family that has been murdered, and he must perform surgery through the night to give them a chance to return to life in the morning. Did the premise come first in this book? Did you have that in mind before you had character, setting, theme, plot? Or was something else first?

VP: The initial idea of Night Theater came to me in a flash. I remember seeing a clear image of a dead family standing in the doorway of a clinic, on the verge of stepping in and plunging the doctor within into a medical, moral, and existential crisis. The one aspect that was clearest to me was the mental state of the doctor, and the mixture of terror, incomprehension, reluctance, and medical obligation that an event like this would provoke in him. Once that premise was in place, it then became a process of building the story from the inside out, creating a skeleton firm enough to grant it structure and solidity, attaching muscles and sinews that would give a locomotive momentum to the plot, and then pouring in the characters and their motivations to make its blood flow. Forgive the resurrection metaphors—force of habit!

SS: Your medical background was put to good use in this book’s detailed description of surgery on the sort-of-living dead. Was additional research required? What did that entail?

VP: The anatomical details relevant to the plot of the novel are largely familiar to every doctor—irrespective of our specialties, we learn it as part of basic training in medical school, and one certainly needs to be conversant with it even in non-surgical disciplines. As for the surgeries themselves, one unusual influence for me was the fact that that my father is a surgeon, and when I was a child (this was in Mumbai), he would often take me to the operating room with him, and I would stand on a footstool some distance from the table and peer at appendectomies and hernia repairs. The youngest I remember doing this was when I was eight. So, even though I’m not a surgeon myself, the basic mechanics of surgeries are sown almost into my DNA. Perhaps the aspect of the novel that needed the most careful work was getting a very clear idea of what kinds of surgeries would be feasible for one surgeon, working without an assistant, to perform in the middle of the night with very limited equipment in a village clinic. That required reading, thinking, puzzling through plot choices, and several discussions with my father.

SS: Are you aware of the connection between Night Theater and Franz Kafka’s The Trial? I’m thinking especially of the afterlife officials in your novel existing in a never-ending, mysterious, bureaucratic hierarchy, but also of a main character being tested by impossible circumstances, with no good outcome presenting itself.

VP: Absolutely! Kafka was a key inspiration for me not just in the conception of the afterlife (where the homage is obvious), but, as you (the Kafka expert!) have astutely noted, in the overall construction of the circumstances of the tale. Kafka was a pioneer in this kind of plot construction—stripping his characters of any foothold on which they might build a logical picture of the world. There’s a constant sense of destabilization in Kafka, a sense that there is no reality or objective truth, and that the floor can be snatched away from under the protagonist, leaving him suspended over an abyss. For me, this form of story provided a powerful experimental arena—could I place a cynical, almost nihilistic, surgeon in this type of mental space, and see if the pressure-cooker of an impossible challenge would break him or help him locate, in his role as a doctor, a kernel of humanity?

SS: One of the themes in Night Theater is corruption, in medicine and in the world of spirits. Did you set out to explore this? How crucial is the setting to this exploration—rural India rather than in a city, or in India rather than somewhere in the United States or elsewhere?

VP: Corruption is a fact of life in India. It is impossible to function in any meaningful way without being willing to pay a bribe. Need a water connection installed? Need a permit to build a home? Need a signature on a government document? Be ready to slip a few (or many) bills here and there. Corruption has also infiltrated much of the medical field. The expectation now in India is that a specialist will pay a kickback to the family doctor who refers him patients, and will in turn receive kickbacks from the radiologist to whom he refers for CT scans and the pathologist to whom he refers for blood tests. In an eroded system of this sort, how is a patient supposed to believe that the procedures she is receiving are medically warranted, and not just another twist in a corrupt pipeline? I saw so much of this around me in India that it became inevitable that it would form one of the core themes of this story. It quickly became the primary moral struggle on which the surgeon’s entire life turned, and also connected with the Kafkaesque dimension that you identified.

SS: Night Theater is a taut, suspenseful tale (while reading, I found myself scanning ahead on the page with worry about what would happen next and had to remind myself to slow down and enjoy the prose). Yet, it is a literary rather than a commercial work of fiction, to whatever extent those distinctions matter. Some commercial novels, as well as big movies and television, tend to tie all the elements together in a neat package by the end, every detail seemingly retrofitted and every question demanding an answer (in the case of blockbuster movies and TV, if not answered by the work itself, then by prequels, sequels, or fans online). Night Theater is comfortable with the discomfort of not answering every question, of not obsessing over world building and back story. How do you feel about that and about the role of the Unknown in fiction?

VP: I’m pleased to hear your experience of the tension of the tale—it certainly was an effect for which I strove. As for the Unknown—that was my companion throughout the writing of this novel. As you know, the ticking bomb of the plot is the idea that blood will begin to flow through the arteries of the dead at sunrise, and the surgeon has to mend their bodies so that they won’t bleed to death in his clinic. Because it was clear that a story of this form needed a tight plot, I wrote out a detailed timeline before I began any work on the language and prose. But I had no idea then what would happen after the dawn, so my plot outline only extended until sunrise, and I found myself rejecting every further path my imagination tried to formulate. For a while, I actually contemplated ending the book on a cliffhanger, just at the moment of sunrise (which would have been a terrible idea!) Eventually, when I found a way to puzzle through the opaque wall of dawn, and came up with a key plot development that opened an entirely new Pandora’s box of conflicts, dilemmas, and stakes for the characters, I also found myself absolved of the need to then go further and wrap everything else up in a bow. In fact, I felt absolutely no discomfort in leaving the reader with a range of disquieting, unresolved questions at the end of the novel. I believe the Unknown in fiction works best when it taps into a deeper Unknown that’s already lurking in the heart of the reader. I hope I’ve been able to tap into it.

SS: Speaking of the Unknown, here’s the question writers dread: you’re busy promoting Night Theater and being a doctor, but what’s next for Vikram Paralkar the writer? Are you working on anything new?

VP: I’m working on a new novel about an eyemaker who crafts prosthetic eyes, and who can see the past and future of his clients. Medicine, Fantasy, Time. I wish I had much more of the latter myself!

SS: I already want to read the eyemaker novel. Good luck writing it, and good luck on Night Theater. It deserves to be widely read. Thank you for talking with me. I enjoyed this.

VP: I enjoyed this as well, and thanks for founding Write Now Philly. It’s fantastic to see the flowering of literary life in Philadelphia in recent years, and you’ve just planted another sapling!

Scott Stein is the author of four novels: The Great American Betrayal, The Great American Deception, Mean Martin Manning, and Lost. His writing has appeared in The Oxford University Press Humor Reader, McSweeney’s, Points in Case, Philadelphia Inquirer, National Review, Reason, Art Times, Liberty, The G.W. Review, and New York magazine. Scott is Teaching Professor of English at Drexel University, Director of the Drexel Publishing Group, and Founding Editor of Write Now Philly. He tweets @sstein.