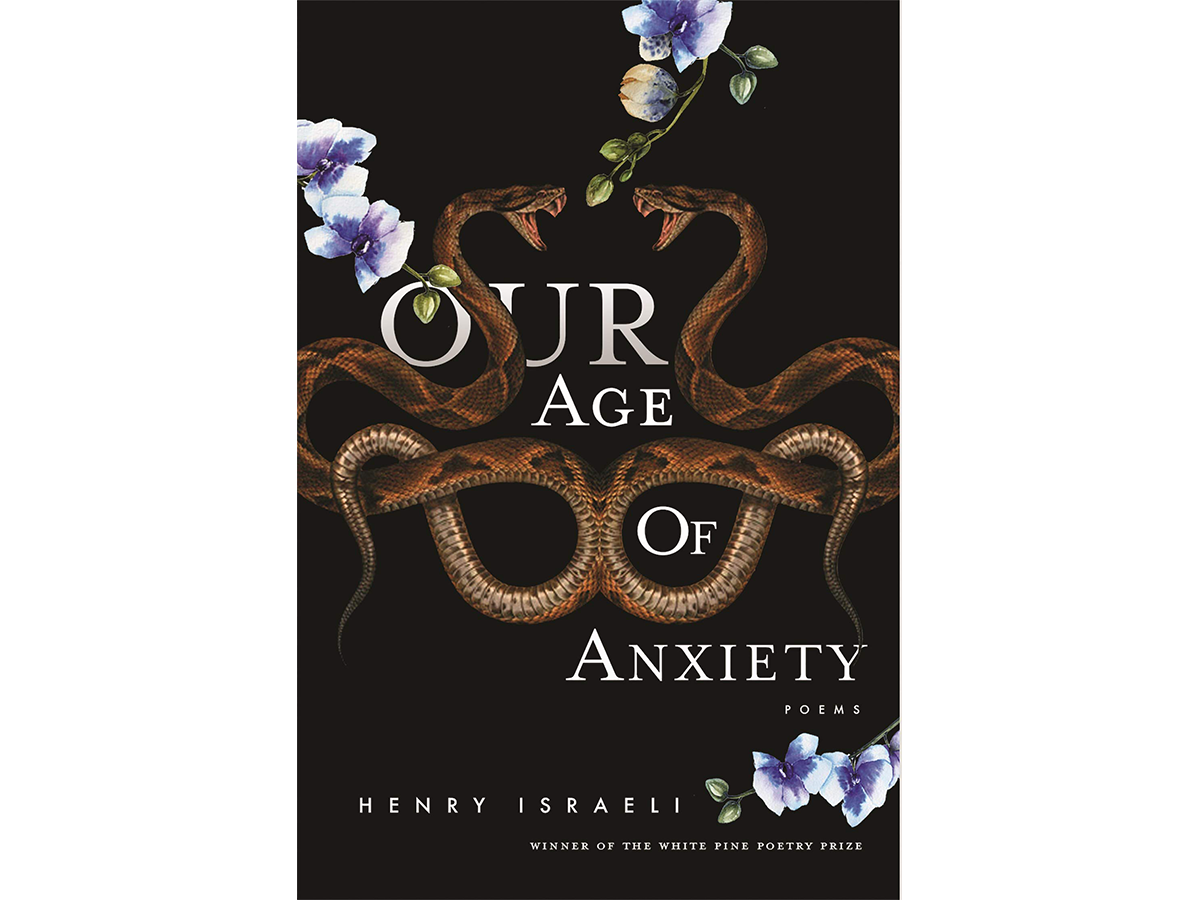

Clever, vigorous, Our Age of Anxiety, Henry Israeli’s latest collection, won the august White Pine Poetry Prize last year. Perhaps because the author is an immigrant, Age takes an angle separate from that of most poets writing in this country at this moment; for that alone it’s valuable. So are the many journeys on which it invites us.

Israeli has a BA from McGill University and MFAs in poetry and in playwriting from the University of Iowa. He is now an associate teaching professor at Drexel University and directs the Drexel Writing Festival. His page on poetryfoundation.org quotes a Massachusetts Review interview in which he says, “As an immigrant I see my adopted home from the perspective of the Other. Now more than ever, in this new golden age of greed, lies, and corruption, I feel displaced. … ” Here is yet another immigrant poet—a few who come to mind are Joseph Brodsky, Ilya Kaminsky, and our own John Wall Barger—whose work invigorates our poetry by standing, as it must, apart.

The title inevitably echoes W.H. Auden’s 1947 Pulitzer Prize-winning poem. And let’s face it: anxiety is the most-reported psychiatric complaint of this our age. But Israeli’s collection takes little more than the title from Auden. This collection of lyrics embraces our culture whole and explores our causes for worry in a worrisome time.

Those causes are many: fear, pain (the masterful “ ‘Pain Is Never Done’ ”), death, the dead, failure, missed opportunities, nothingness (“In Rat’s Alley”). Generational conflict is high on the list. In “Rebirth,” one of the collection’s best, the speaker’s father

returns as a fox

scrambling to get off the road

and into a copse. He looks up at me

passing by in my Highlander

for a fraction of a second, confirming

his suspicion that I would never

live up to expectations.

In “Blame the French,” we can’t escape influence, or at least so we fear:

Everything you’ve done

in the bedroom—

I’ll simply say, the French,

and waste no time

humiliating you further.

There’s humor, irony, and a constant undertow of submerged violence, as in “Book of Shoulds”:

Taken out of context

the river’s always looking for new

ways to strangle us.

Several poems end with portentous images that carry their own reversal, as in “Turn the Key Deftly,” in which the speaker contends with a voice from the other side:

There’s no pain now, he tells me, although he

no longer has a face

but a hole the size of a face

where his face used to be

and when I reach deep inside it

my fingers wrap around a pistol—

its hard, cold grip making my hand feel

alive for the first time.

This is declarative, rhetorical verse. Loaded titles abound: “Rebirth,” “The Fathers Show No Mercy,” “Love Poem to Albert Speer,” “E Pluribus Unum,” “The End of Theology,” and at least three titled “Our Age of Anxiety.” Can the poet live up to them? Israeli does often enough, thanks to his deeply playful orchestration of myth.

Ours is a time for myth-making; many a poet, including Barger, and also Israeli’s Drexel colleague Lynn Levin, is seeking to hit on the myth for this impossibly provoking moment. Often brilliant, Israeli’s myths harbor an obscure explosive potential. The gun’s knack for havoc makes us feel alive, but we don’t shoot. The river may be plotting our demise, but we don’t drown, we worry we might.

Several stories are Matryoshka Doll-like, framing and reframing. I can’t pretend some frames aren’t too elaborate. In some poems (the opener, “Birth of the Machine,” strikes me this way) they get too obviously deliberate. In a cherishable core, however, including the reincarnation of “Rebirth” and the exquisite “Blue Orchid,” the myth is beautifully negotiated.

Repetition abounds: blue in “Blue Orchid,” the title phrase in “Man with a Dog’s Head,” interrogative openers such as “Have you seen … ?” in “New Year in the Old Country” or “Who walks … Who touches … Who shouts … Who burns … ?” in “The Fate of a Boisterous City.” Anaphora, symploce, and all their cousins are here aplenty. This recalls Nietzsche and Freud on compulsive repetition as a symptom of angst.

And the allusions!: Eliot, Hopkins, Keats, Duchamp, Speer, Testaments Old and New, lots of French artists, Shakespeare, Stalin, tarot, and more. Never just name-drops, these enrich their poems. This is poetry that likes the surreal interruption of capital letters, of Rome, of Wednesday, of the butterfly Vanessa Cardui.

It’s a splendidly neurotic universe. Granted, the poems may sometimes know a little too much about where they want to go and what they want to do. But with all the worry flying about, Israeli as poet is not very worried about intentional set-ups. They are invitations to deep play. And that can lead to many pleasures—the acid smile: the metallic surprise; the fruitful disappointment, redirect, or reversal; the tender moment (a couple) in a ruined landscape.

Which leaves us with the closer, “Blue Orchid,” the quietest, tenderest poem here. It’s a treat to read aloud, the slower the better. The speaker curls up in bed, and the petals of an immense female orchid form a womb in which the speaker and all the living and all the dead

sleep in her grasp,

our blue dreams lifting us into the blue night.

It’s an amazing moment. Our Age of Anxiety sings us a lullaby and puts us to sleep. As if the anxiety could ever be over.

Our Age Of Anxiety

by Henry Israeli

White Pine Press

Published on September 3, 2019

104 pages

John Timpane, the former Books Editor and Theater Critic for the Philadelphia Inquirer, is a retired English teacher and journalist living and working in New Jersey. His work has appeared in Sequoia, North of Oxford, Apiary, Painted Bride Quarterly, Schuylkill Valley Journal, Per Contra, Vocabula Review, Truthdig, and elsewhere. His latest book, a chapbook, is Buck in the Piano Room (Philadelphia: Moonstone Press).