How can we heal ever-fresh wounds? Julia Kolchinsky Dasbach explores grief, family, and generational trauma through the lingering effects of the Holocaust on Eastern European groups in her poetry collection, Don’t Touch the Bones. Rather than sit in a place of mourning, Dasbach explores the vacancy left by the genocide, and how it still bleeds through the present. Writing through the elements of water, fire, earth, air, and even the æther, she finds this void in all places, writing of “the same story” over and over. It is when Dasbach arrives past the elements and into the body that she finds this continuation in “the endlessness of bones.” How can this vacancy be filled in a catastrophe where bones are still found? Dasbach doesn’t know the answer but she ends with an ode-like poem to the body; “praise these your tiny bones,” the remnants, the body, is not something that leaves a burden, but reminds us of how to live.

Leading in Dasbach’s first section “In the Earth,” is a poem with the same name as the collection: “Don’t Touch the Bones.” In this poem, she reflects on the sum of what is covered throughout the book. Repeating the line “writing the same story,” Dasbach is aware of her repetition in the stories she covers. At the same time, she is also aware of the generational trauma that runs through Jewish families, making this repetition a crucial marker for the themes she covers rather than a redundancy. The same story over and over is all that is left when bones are still being dug up. She reflects on this longing, associated with family and culture. Switching between these domesticities of life with “matzo” and “honey,” then thrashing into the violence with the line “where her wedding band would thaw to bullets,” Dasbach plays with the trauma that bubbles up within day-to-day familial life. As done in this poem and many to come, Dasbach switches between grief and the simple moments of life. This allows her poems to cover a range of emotions, reminding the reader that there is good in the bad and vice versa.

Moving on to the “In the Air” section, it opens rather Gothically with “In Praise of Forgetting.” The poem, as the title suggests, praises the forgetting of mundane objects associated with the home, which are morphed into ghastly images themselves.

“Forget street numbers and front doors and languages of all the ones // you’ve lived in before”

Dasbach aims to move on, to live without memory of little details that haunt the house. She writes of the ghosts that “are houses inside of houses.” Domesticity here, takes the place of a void, something that is lost because of memory. If the idea of home is itself a ghost that haunts her, how can Dasbach move past a longing feeling? The poem executes this fleeting and wispy mood beautifully, taking that comfort of a home and turning it into a labyrinth.

The third segment, “In the Fire” finds the dichotomy that flame holds of pain and light. This is explored in “Fire, Fire,” as Dasbach writes of her son alongside the victims of the gas chambers at concentration camps. Following that theme of generational trauma, she sees that there is a fire in her son’s hands that “singes the air.” With the fire comes the ash of those victims that the son carries, which is “eternal” and “unnoticed”. Dasbach further writes about the effects of the poems to soar. It provides for a rich and diverse read with different themes for the reader to latch on to.

Dasbach breaks into a meta area with “Driftwood Pantoum,” contained in “In the Water.” She recalls her mother telling her that an unknown she is “turning in her grave” each time she writes of her. Dasbach is aware that it is not her story to write but she can’t help but write of the stories that haunt her when she closes her eyes. Allowing her own personality to come through here is refreshing at this point in the work, as much of the collection references the people around her. It brings about a loose conclusion, not of the grief, but of a final charge into the effects of the Holocaust. It has affected her family and it, too, affects Dasbach.

The transition into the next two sections “In The Æether” and “In the Body” are paired brilliantly. Dasbach writes of this fifth element that humans cannot contain. Moments of grief, praise, and reflection have run through all the elements covered in the collection. Arriving past these and into the æther, Dasbach suggests that these feelings exist in an unexplainable almost supernatural form. Yet, the arrival and conclusion in the body ends the work on a satisfactory note. The same feelings that were just in an intangible place, now exist in a familiar space.

From the æther and into the body becomes a reclamation of what Dasbach could not understand, the answer she was looking for in the collection was contained inside her and inside her Jewish ancestors. The collection ends not with anger, but with praise. In “Phalanx Bone Shehecheyanu,” Dasbach praises the bones that she wrote of in the past collection, the ones that are being found and the ones that are contained inside her. Because with these bones, with the praise, the memory can live on in a brighter note.

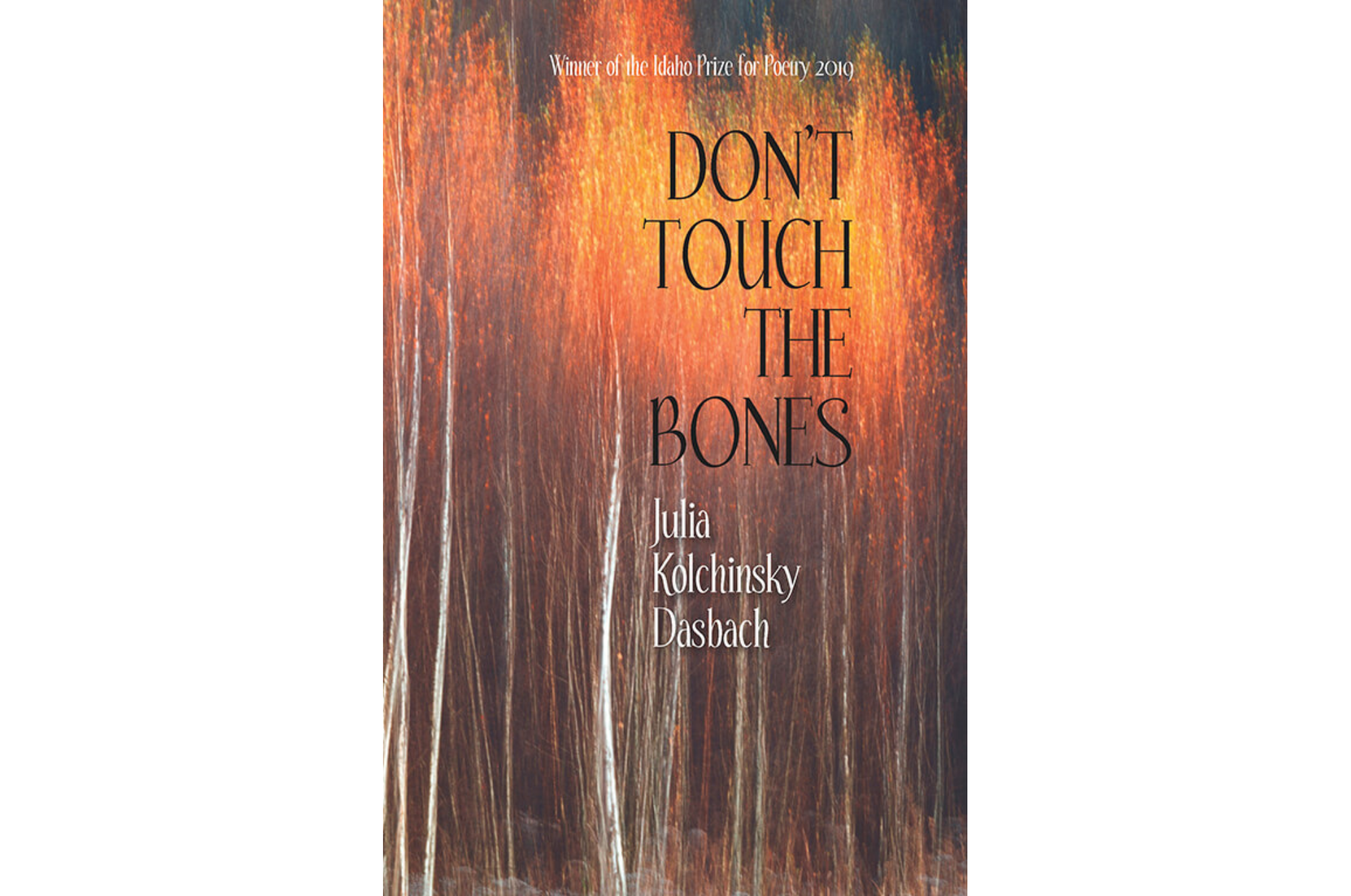

Don’t Touch the Bones

By Julia Kolchinsky Dasbach

Lost Horse Press

Published in March, 2020

86 pages

Michael Emmert is a second-year student at Drexel University, looking to obtain a bachelor’s degree in English with a concentration in writing. Outside of classes he likes to walk around Philly finding coffee shops and sketch things in his journal. In addition to writing, Michael also has a love for plants and drawing. One day he hopes to publish an eclectic book, blending mediums including poetry, art, and memoir.