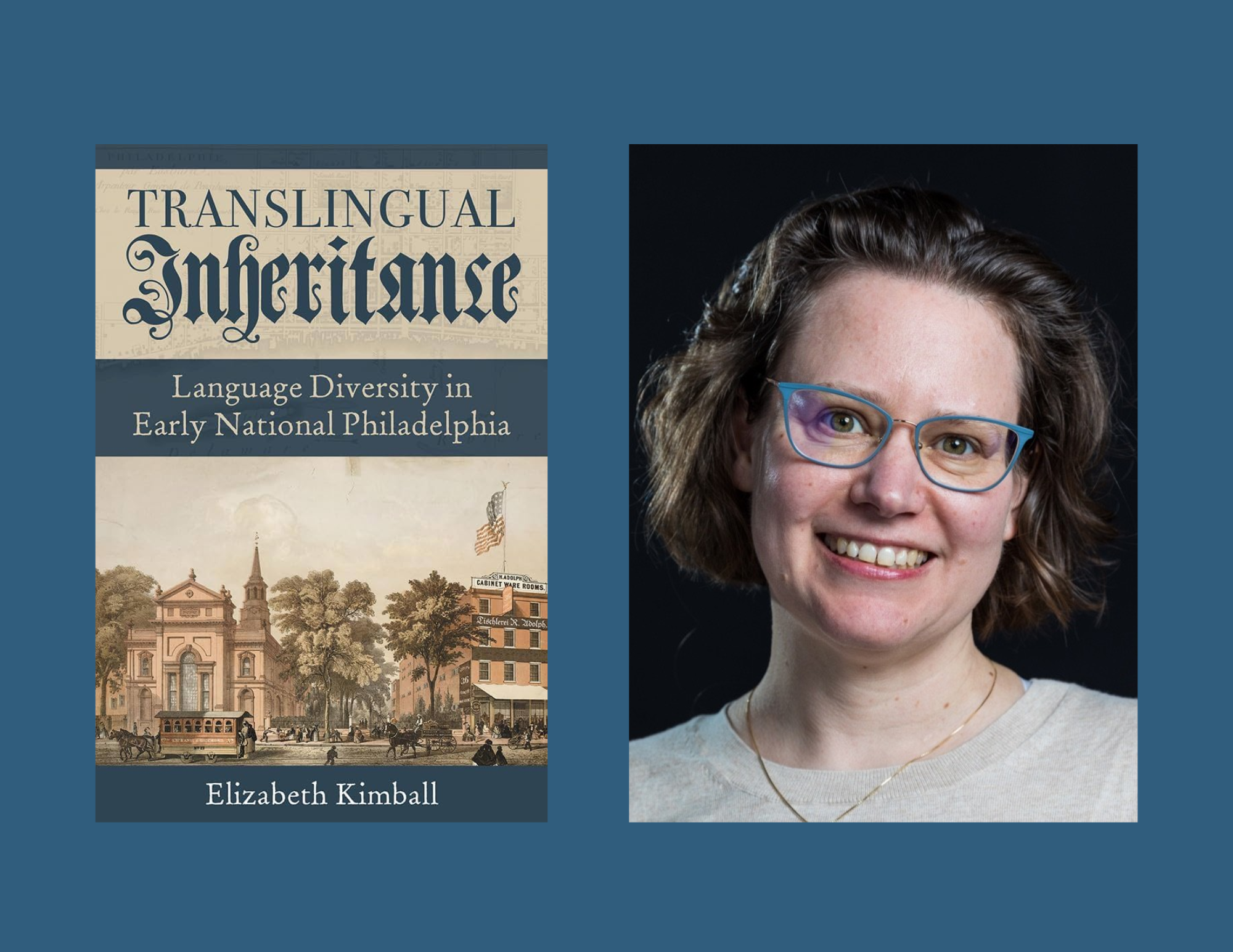

Elizabeth Kimball is the Director of the Writing Program and Assistant Professor of English at Drexel University, where she teaches courses including first-year writing, writing and rhetorical theory, community-based learning, and graduate teaching in the MFA program. Kimball’s book, Translingual Inheritance: Language Diversity in Early National Philadelphia, was published in 2021 by University of Pittsburgh Press.

Nicole Marie: Have you always liked to write?

Elizabeth Kimball: Yeah, I think I have. I read very early, and teachers saw that literacy was my strength. I had a teacher in sixth grade, when we started writing more independent things, and she did a lot of really fun stuff around a social studies curriculum. She was Greek American, so she was really interested in all the classical stuff we learned that year. I remember her pulling me aside and saying, “You’re a really good writer, you could keep doing this,” and that was the first time, I think, someone gave me individual attention. I didn’t know teachers would even speak to students individually before that and ever since then, I saw it as one of my strengths.

NM: Regarding your book Translingual Inheritance: Language Diversity in Early National Philadelphia that was published in 2021, what led you to write about language diversity?

EK: I had always been in English departments through all my degree programs—undergrad, Master’s, PhD—and English departments, by definition, focus on literature written in English. Meanwhile on the side, I think the most meaningful and challenging experiences I had were in languages other than English—being a language learner. I participated in a study abroad program in Japan when I was in undergrad, and it was really immersive using Japanese all the time. I was an assistant English teacher in a middle school, so I was totally immersed in the way that the education is set up in Japan, just understanding how fundamentally different orientations are that you don’t realize. It’s not just a simple question of translating, it’s a totally different way of seeing the world. So, I had done that, and I had done some translation projects from Spanish, I did a bunch of study in Central America, and it just kept striking me as I was developing my dissertation project in rhetoric and composition. We talk so much about the teaching of writing and try to blow it up in all these important ways, not just take it for granted, not just do what’s been done because it’s traditional. We never really have challenged the fact that we just talk about writing in English. We just assume that everything in the U.S. is monolingual unless told otherwise. Unless you’re dealing with immigrant students or unless you’re dealing with international students, it’s totally monolingual and it just struck me: why are we so blind to that? So that was the start of it; it was my dissertation project, which I then turned into a book.

NM: What was the hardest part about writing the book?

EK: Investing the time knowing it might not get published. It really had to be completely done before I could get a contract. This is academic writing, so it’s a whole other publishing world. If you’ve already published an academic book, you might be able to get a contract for a book just based on the prospectus or a couple chapters, but this, I really had to write the whole thing. I would send it to publishers, and they’d be like, “Yes! Sounds great! Send us the manuscript.” That was really scary, and then it was also really scary because my job at Drexel was basically dependent on it being published. So, getting a rejection isn’t just like, “Oh, that sucks,” it was like “Oh crap, my whole livelihood and everything I’ve planned in my life will need to be totally changed!”

As far as the writing of it, when I wrote the dissertation, I was kind of making up some of the theory of being multilingual, and I didn’t know if I was ignorant of what was out there or if I was grasping at something no one else had really thought of. Right after the dissertation was done, the whole translingual research movement kind of emerged really quickly in 2010. That was actually kind of useful—like, “Oh, that was the theory I needed, and now there’s a body of work that I can both borrow from and enter into.” So, I was able to say, “Yeah you have this translingual theory, but you haven’t thought about it historically,” and that’s what my book does.

NM: What did you learn about writing as a practice overall while writing this book?

EK: Somebody referred me to a book called Writing Your Dissertation in 15 Minutes a Day, which is a deceiving title, because you can’t actually write your dissertation in only fifteen minutes a day. But the idea is that every day, you spend at least fifteen minutes checking with the project and journaling your writing. Every day, you keep a little journal of like, “Where am I with this?” “What idea am I working on right now?” “What am I going to do today?” “How did it go yesterday?” at either the beginning or the end of each writing session, so that you’re constantly checking in with your own thinking about it and keeping it at the front of your mind. So that, even when you’re busy, you don’t forget that it exists. That’s what I have tried to do ever since, with more success some years than others. All the other research I have read since about writing says that it’s like what they say about a savings account: don’t wait until the end of the month to see how much money you have left over to put into your savings account. Put it in first because the interests that compounds will make so much more difference over time. If you spend thirty minutes every day that’s better than spending like two and a half hours only on a Friday.

NM: What is at least one insight you hope readers take away from your book?

EK: I think the main argument that I make is don’t assume that when you’re looking at the history of the United States that the “diversity” only exists in the margins. From the very beginning we were a country that was interacting from places of difference. It was never just a bunch of white guys from England all being the same. Even those guys were different among themselves. So, being a diverse society is fundamental to what the United States is, and we need to own that because there’s too much ideology out there that says it was a bunch of white guys first and then a bunch of other people came later—no, the United States was diverse from the beginning, from before the beginning.

NM: Moving into your other roles, as director of the Writing Program, what is your favorite part of the program or initiative you’ve started?

EK: Well, I have to say the Peer Readers. I really love the Writing Center and what the Peer Readers do. I think you have a community and an energy that is special for Drexel, making it bigger than just writing consultations. That’s really what I want, the community that you all create. We need more of it at Drexel across the board, among faculty and among programs and within our classrooms.

NM: How has being a professor impacted your writing or view of writing when working with students?

EK: Because I’ve seen so many students over a long time and so many pieces of student writing, I think it’s taught me that there really isn’t anything to be afraid of. I think of when I first started teaching, I would have students who struggled with writing and in the back of my head, I might secretly worry, “What if they really can’t figure it out?” Now, after all these years, I’ve realized there’s a set of tools that can be learned and there’s hardly anyone that can’t do it with enough practice. I think most people fall short because they just don’t give themselves the hours you need to get good at it. I was reading an essay about becoming a writer by a novelist the other day, and he was talking about when he was a teenager, he wanted to have a rock band. He was saying that if you’re starting out as a musician, you have no expectation that you’re going to make it to Carnegie Hall. People that start out wanting to write, wanting to be a novelist, they think, “Oh, I’m just going to crank out this novel and then the world should publish it. If it doesn’t get published, it’s the world’s fault,” instead of recognizing it takes a really, really long time to get good at writing. As you develop, you’re always getting better. I think most people can learn it over time with enough practice and good teaching.

NM: From a broad perspective, how has writing impacted your life?

EK: As I’ve gotten older, I’ve realized if I don’t have some writing in my life, there’s a gap; there’s something missing and I get cranky. As long as I’m wrestling a little bit every day with something I’m working on, even if it’s not going great, it’s still something my brain likes to do. Some people, the thing they need to do every day is run ten miles or something; I have no desire to do that, but writing is something that I need to have in my life.

NM: Do you have any advice for young writers?

EK: I would say to try to find people who will read your writing and can have conversations with you about it, along with reading their writing as well; as this will improve your writing, and have an even better experience. I really found that a lot of my book happened because I’ve found a really good writing group, and they gave me really good feedback. Because I trusted them and we became very good friends, they could tell me when it wasn’t good. They didn’t need to say it explicitly, but they could give me good advice and help me see it in a new way. I also didn’t feel like I was alone, I felt like someone was paying attention to what I was doing. It was just really important so I would say, seek out as many writing friends as you can and start writing groups.

NM: Is there anything else you would like to share about your work or elaborate on anything else you talked about?

EK: I think that academic writing is actually just as fascinating as creative writing. I think that’s something that we don’t spend as much time talking about at Drexel. I think a lot of students could learn to see all the creativity that goes in, even though the genre doesn’t sound like a creative genre. I think that’s why I’m in academic writing.

Purchase Elizabeth Kimball’s book Translingual Inheritance: Language Diversity in Early National Philadelphia here.

Nicole Marie (she/her) is a third-year student at Drexel University pursing the Accelerated BS/MS in Psychology program while minoring in Writing and Neuroscience. On campus, she works in research labs, the Writing Center, and is the Chief News Editor for The Triangle (Drexel’s independent student newspaper). In her free time, she enjoys being creative through painting, journaling, and crocheting. After graduation, she hopes to pursue a Ph.D. to become a Clinical Child Psychologist.