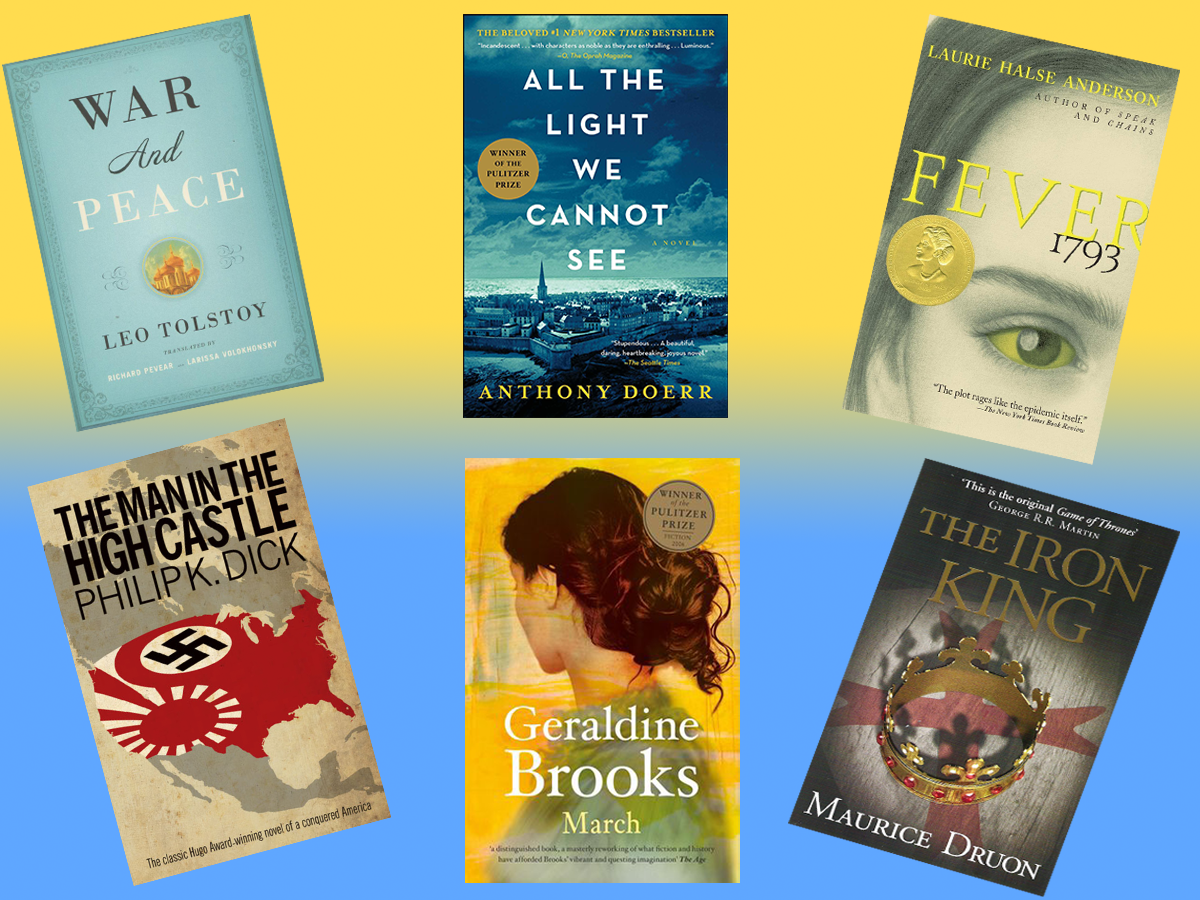

With the world engulfed in the COVID-19 pandemic, I find it therapeutic to crack open a book that can whisk me away to a different time or place. Recent bestsellers like All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr or even classics such as Tolstoy’s War and Peace tell stories from the past, transporting their readers in a literary time machine. While it may seem strange to “escape” into books that are set during other calamitous events, such as World War II, these stories are often ones of triumph in the face of overwhelming adversity. Whether the setting is war-torn Vichy France or the Russian Revolution, they can simultaneously inspire and teach their readers, as well as invoke reflection and elicit emotion. As a fervent reader of historical fiction, my favorite aspect of the genre is how authors can familiarize readers with a reality that is drastically different from their own, engulfing them in the minutiae of an era. How writers envision and construct their setting, characters, plot, and dialogue is essential to not just telling a story but painting an accurate picture for readers like myself.

Historical fiction is, by definition, an imaginative reconstruction of the past. Although many authors include famous historical figures and events as backdrops for their stories, the only real requirement is that the piece in question is set sometime in history. Historical fictions are not only fun and interesting, but incredibly useful and educational. They engage readers by weaving narratives through history, creating characters we can learn from and relate to, even in the past. Laurie Halse Anderson’s Fever 1793 is a staple in many U.S. middle school curriculums for these very reasons. Other subgenres of historical fiction include alternate history or historical fantasy, both of which overlay real events with exaggerated elements. Alternative history, like Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, ponders the society we would live in had historical events transpired differently. Historical fantasy, on the other hand, takes historical accounts and embellishes them with fantastical components. Examples of this date back thousands of years, from the Battle of Troy in Homer’s Iliad to the life of King Arthur in History of the Kings of Britain, a 12th century novel written by Geoffrey of Monmouth. George R.R. Martin, famed author of the fantasy series A Song of Ice and Fire, is especially fond of this cross-over, writing in a foreword for an edition of Maurice Druon’s historical fiction novel The Iron King: “I have always regarded historical fiction and fantasy as sisters under the skin, two genres separated at birth.”

While there is so much room for creative and fictitious embellishment, historical fiction has to be, above all, accurate to the time period being presented. Geraldine Brooks, a Pulitzer-Prize-winning author and journalist, said it best in an interview after the publication of her prize-winning novel, March. “The thing that most attracts me to historical fiction is taking the factual record as far as it is known, using that as scaffolding, and then letting imagination build the structure that fills in those things we can never find out for sure.” To ensure writing is capturing the “feel” of the era, authors pay close attention to the “scaffolding”, i.e. their characters and their behaviors, their dialogue, as well as the spaces they inhabit. Accuracy within historical fiction relies on extensive research of the actual setting and/or conflict that the plot is based around. Author and blogger M.K. Tod suggests in her blog A Writer of History that reading relevant literature of a topic by reputable historians, exploring primary and secondary documents from the time period, watching movies, listening to music, and examining art from or about the time period are tools that many authors use.

It is equally important to readers that an author knows their characters as well as their limitations within the chosen timeframe. Any character, whether it be main or supporting, should behave in a manner that suits the era, even if they push the boundaries. If a character is a peasant farmer during the Russian Revolution, they are not going to be acting like an aristocrat. They’ll have different mannerisms that are influenced by their education, socioeconomic status, rights, and beliefs. Oftentimes, having a character learn a skill or trade that would otherwise be inaccessible to them tells a lot about a character and distinguishes them from the rest. For instance, maybe this Russian peasant farmer has learned to read despite their lack of access to formal education. Sure, historically it’s unlikely, but that is the freedom of fiction. If every farmer in the village were to read, however, it would be grossly inaccurate to the level of education expected from a Russian peasant in the early 1900s—something an avid reader will notice.

Furthermore, nothing will make readers feel like they’re in a different period of history more than the dialogue. If a character is a plucky kid from East London who works in a factory during the Industrial Revolution, the dialogue will be essential in distinguishing that character. Including slang terms and words that capture the accent will only serve to enhance the reader’s experience and further envelop them in the world being built around them. However, authors warn of dialogue becoming too complicated or cumbersome. M.K. Tod also argues that writers should be sparing and thoughtful when imitating the grammar and vocabulary of the era, using enough to capture the tone but not so much that it becomes too difficult to follow. As a reader, it can be frustrating to constantly consult a glossary in the back of the book to understand what a character is saying.

Lastly, good historical fiction pays close attention to the details. When writing historical fiction, it is not as easy as simply stating that these events are taking place in the past—readers want the story to come alive. What is the character seeing as they walk through their city? What do they smell? What do they hear? What are other people doing? What is going on in the news? How much does something cost? These are just a few of the many aspects of everyday life that have drastically changed in even the last twenty years, let alone the last two hundred. Including elements of the story that are not integral to the plot but contribute to the setting are details that people might not even necessarily notice but will inevitably contribute to their reading experience. On the other hand, all it takes is one inaccurate or misplaced detail to jerk someone out of the story and back into reality.

Charles Massey is a senior at Drexel University studying Anthropology and pursuing a Certificate in Writing and Publishing. He enjoys reading, writing, supporting Liverpool Football Club, and walking his dogs down by the Schuylkill.