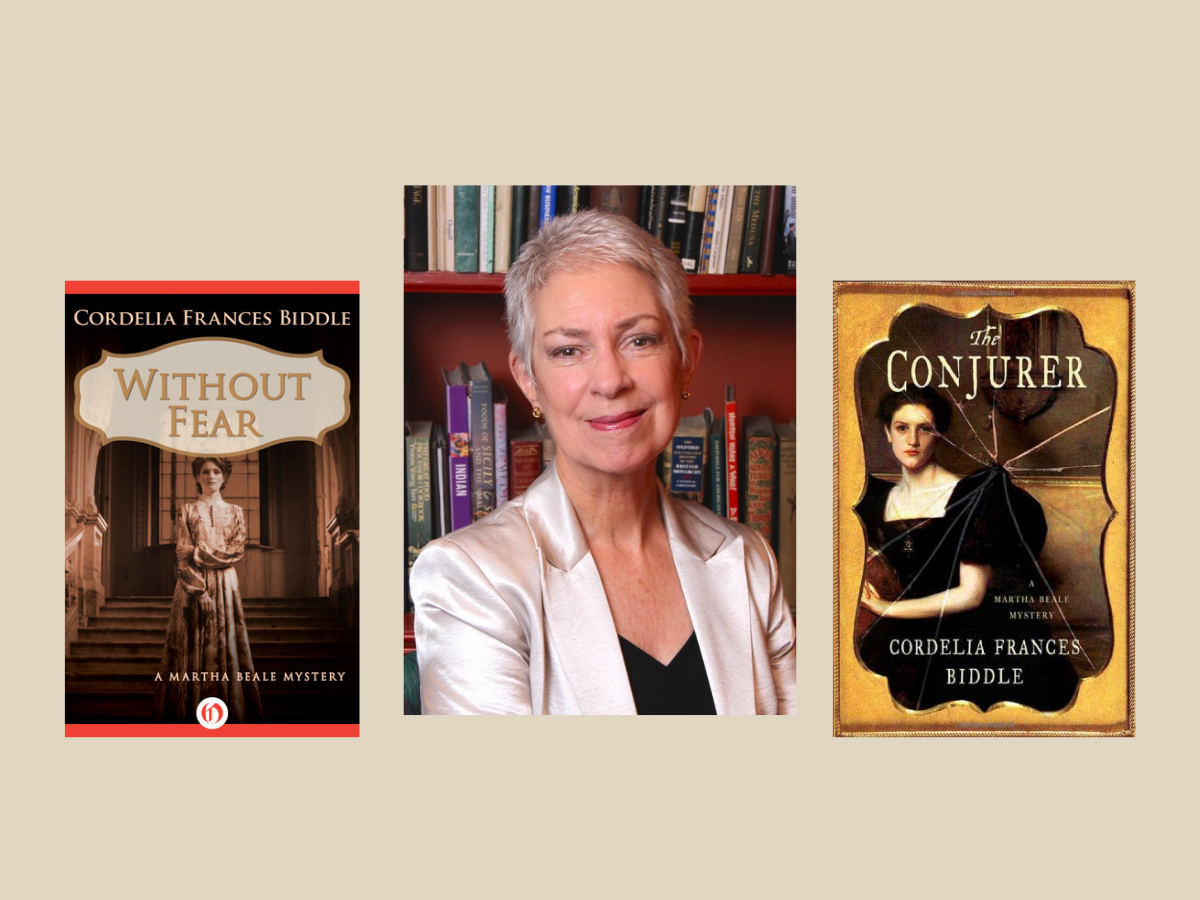

Cordelia Frances Biddle is a Philadelphia-based author who teaches in the Pennoni Honors College at Drexel University. She has written both fiction and nonfiction books, many of which have fundamental historical components to them. In addition to teaching, she was previously an actress working out of New York, and she was a journalist, writing for magazines like Town and Country. Some of her books include Without Fear, The Conjurer, and the 12-novel saga, The Crossword Mystery Series, which she wrote with her husband, Steve Zettler.

I had the opportunity to enroll in an honors seminar that Professor Biddle taught. Following my time in that class, I spoke with her about her experiences throughout her career; during our virtual interview on February 22, 2021, she shared insights, memories, and advice for writers.

Pooja Balar: Thank you very much for taking the time to have me interview you today, Professor Biddle. To start things off, could you tell me a little bit about yourself?

Cordelia Frances Biddle: This is going to sound very odd, but the reason that I teach is because I had a grade-school teacher who discouraged me from writing. She said ‘Oh, you have no imagination, so you can’t ever be a writer.’ So, at the age of ten, I believed her! And I thought ‘Oh, I’ll never be able to be a writer because I have no imagination.’ But I’ve always had a vivid and weird imagination. But she discouraged me, so I became an actress instead. And it was while I was working on a soap opera in New York that I started writing my first novel… I was listening to this soap opera dialogue all day long… But I had this idea, and it was gripping me, and it wouldn’t let go, and so then I’d go home and rewrite everything I’d written all day long. And that was published, and then I said, ‘Oh, wait! I am a writer! And so, I then changed my entire career. However, I have always gone back and understood that what I understand about writing is really through acting. So, I see the writer as not only the author, who has created the story, or the story has come to them, or if it’s fiction I created, if it’s nonfiction I’m dealing with, the set circumstances in historicity, but I see myself as both the author, and the performer, and the set designer, and the costume designer, and the researcher, so I see that is how I view my role as an author, all of those things. So, it’s not simply words, it’s the visual, it’s the sound. If I could make my novels into films, I would know how they sounded, I would know how the food tasted like. And that’s when I was working with all of you, I said, you know, really, let’s get those specific details. Be very specific, it’s not just about words, it’s about how the words taste in your mouth, and how they smell, and the sounds they make. And I am very fussy about my writing, and I will go back and back and back over one sentence until it sings. And what that means, I don’t know, except that I know when it sings and when it sounds clunky.

PB: You’ve published many books, several series even, following your first novel. What themes and genres do you find yourself gravitating towards when you start to write?

CFB: My series is set in Philadelphia in the 1840s. In those, I explore the chasm between wealth and poverty, which was huge, as well as a woman’s place in society. And so, I have an iconoclastic heiress who goes against the grain. She enters into situations that she would ordinarily not have been permitted to enter into. And my reason for those novels and that particular era is because I knew a great deal about the Civil War in Philadelphia and the Revolutionary War in Philadelphia, I mean it’s drummed into our heads, I didn’t know about that cusp era, and I didn’t realize how much—there were race riots, there were, I mean, people were living in enormous poverty… So, I wanted to explore that, I wanted to expose it, and I didn’t want to simply stand on the soapbox… So, let me cloak it in murder mystery, let me cloak it in something that is romantic, tragic—everything I write is always tragic—and let me give it sort of a pastiche, another kind of a genre. And, I’ve had a wonderful time writing them, because I do get to expose what I see are the true failures in society. My first novel, which was the one that I was writing while working on the soap opera, was inspired by photographs that I had seen of a journey around the world in a private yacht in 1903. And I really wanted to understand what that was like… So, the wealthiest of the wealthy, and there again, I have a female protagonist, not happily married, in fact, very unhappily married, and her discovery of herself. So, there again, it’s sort of a woman’s empowerment novel. It’s tragic at the end—it’s so tragic that it’s still really hard for me to read the last chapter because her husband foolishly gets them involved in a rebellion in Borneo… and she’s trying to flee, and her son, Paul, is shot, while in her arms, and killed. And I knew that I was going to have to have a cataclysmic end because I couldn’t allow her to escape scot-free… So, I had to write this terrible, just excruciating scene, but it had to be done… But in the very beginning, I had her pondering a poem by Robert Browning, and it’s called ‘Incident at the French Camp’. And I thought, I mean it’s something that I memorized when I was a child, but I thought, ‘Why is she remembering this poem—who cares? It’s about the Napoleonic Wars, what has this to do with her life?’ But it kept going into my mind, and I thought, ‘Well I’ll just write it down, and she’d remember a couple of lines, and then she didn’t—Do you think I ever looked it up? No, I didn’t! I simply allowed her to think it through until the very end, which is the last line, ‘Smiling, the boy fell dead.’ And I thought, ‘She knew this from the beginning.’ I, as the author, didn’t know that.

PB: That experience sort of speaks to the idea that the writing process for an author is never as clear-cut as we expect it to be. When you’re in the middle of drafting a novel, what do your planning stages look like, and where do you find your inspiration?

CFB: I always do enormous amounts of historical research, and I love the Library Company, because I can find the real newspaper from any era… And because it’s not just the information, which you could get, probably on, probably not on Google, but you could find, you could go to the Library of Congress and get some of that information. You wouldn’t get the ancillary information, you wouldn’t see the advertisements, you wouldn’t see, for instance, somebody, you know, a runaway slave. And all of that other information, that ancillary historicity, is vital… Inspiration? Really, simply, walking down the street, looking into a window, saying, ‘Who lived there? What was it like? What happened there?’ I’m working on a new novel that is interconnected short stories, going from the earliest days of Philadelphia, so Revolutionary War, British occupation just finished, race issues, early 1960s. It’s sort of a huge gamut of time, but it’s told from the point of view of the house, ’cause I believe that houses have souls. And so, the house is telling you the story, and saying, ‘Well, you don’t think I have your English words, but I understand you. I know what you’re thinking.’ And then, as the story progresses, people who have lived in that house become ghosts.

PB: What can you tell us about your upcoming pieces? What’s about to be published, and what are you currently working on?

CFB: About to be published is the Biddle, Jackson, and A Nation in Turmoil. The one that I’m working on now is the one about the house… I Remember You. So, I labored with that—I’m bad at titles, I know I made all of you write titles. Because they’re important, but I’m terrible at it. And so, it was ‘I Remember’… no that’s not good enough. And so, it needed to have that connection and come forward and speak to the reader.

PB: What advice can you give to individuals seeking a career as an author?

CFB: Just keep writing… It’s not thinking it through and trying to plan, it’s actually putting either your fingers on a piece of paper or on a keyboard and working, because you’re gonna throw away as much as you keep. And I’m very determined in my work schedule. I sit down, and I work. And I sometimes don’t get up and move around, which I’m told I should always do, but I’m in the moment and I’m in the place. And if you don’t do that, if you don’t force yourself to do that, if you don’t force yourself to be, sort of rigorous—I’m not a person who says, ‘Let me wait for inspiration.’ Because inspiration comes from the work. You find the inspiration as you’re writing.

Pooja Balar is a junior in the BS+MD program at Drexel University and is also pursuing a certificate in Creative Writing and Publishing. She loves spending time with her dog, as well as dancing, playing the guitar, and boxing. She’s a Marvel enthusiast and a Netflix fanatic, and when she’s not studying, she’s uploading blog posts on her personal website.